Europe’s breadbasket runs on fertiliser

Central and Eastern Europe accounts for a disproportionate share of the EU’s arable land and cereal exports, cementing its role as the continent’s breadbasket. Yet the region’s agricultural output hinges on fertiliser supply, where energy costs and a small number of regional producers — led by Agrofert — play a decisive role.

Although agriculture employs a shrinking share of the workforce, its strategic importance has only grown. The ability to feed the population remains a core pillar of sovereignty — a lesson underscored not only by Europe’s wars of the past, but also by the Covid-19 pandemic, when agricultural supply chains were abruptly disrupted.

That importance is reinforced by a structural constraint: Europe’s productive farmland is both shrinking and degrading. Soil erosion, declining organic matter and salinisation are steadily reducing yields and resilience. Around 24% of EU soils are affected by water erosion, nutrient imbalances affect nearly three quarters of agricultural land, and urban expansion continues to consume hundreds of square kilometres of farmland each year. These trends have turned agriculture into a long-term strategic concern rather than a purely economic sector.

This helps explain why governments in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) increasingly treat agriculture as strategic infrastructure, not a free market. Policy influence is exercised through land laws, subsidy allocation, support for processing investments and export corridor management. Hungary protects domestic farmland while encouraging outward processing expansion; Czechia tolerates strong consolidation around Agrofert; Romania allows foreign capital while retaining political leverage over the sector.

This series takes a value-chain approach to agriculture in Central and Eastern Europe, exploring how land, inputs, production, processing and logistics together shape the region’s food economy.

CEE’s weight in European agriculture

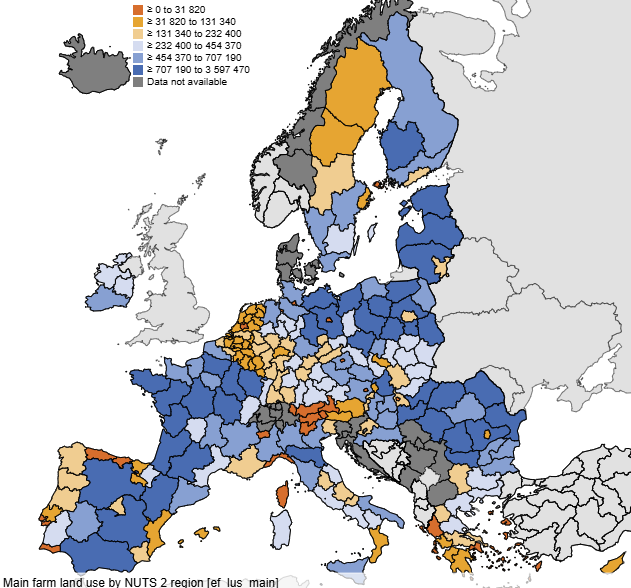

Utilizable agricultural areas

According to Eurostat, the EU manages around 157 million hectares of utilised agricultural area, of which roughly 25–30% lies in Central and Eastern Europe. Two countries dominate: Romania and Poland. Romania alone accounts for about 13.5 million hectares, while Poland manages roughly 14.5 million hectares, making them among the EU’s largest agricultural nations by land area.

The region’s strength lies primarily in arable land rather than permanent pasture. In countries such as Hungary, Czechia and Bulgaria, 70–80% of agricultural land is arable, well above the EU average — earning the region its reputation as Europe’s “breadbasket”.

While France dominates agricultural output and Spain specialises in high-value Mediterranean crops, Central and Eastern Europe underpins the EU’s grain balance through its concentration of arable land and cereal exports.

Land quality across the region

Land quality further differentiates the region. Hungary stands out, with 60–70% of its arable land classified as chernozem or chernozem-like, among the most fertile soils in Europe. Romania combines scale with quality, holding some of the EU’s largest areas of high-grade black soils. Poland offers vast scale but more heterogeneous, often sandy soils, requiring higher input intensity. Czech soils are less exceptional but stable and well managed, while Slovakia’s fertile land is geographically concentrated, making control over lowland areas strategically sensitive.

Regional export capacity

Despite land degradation pressures, the EU remains a net exporter of agricultural and food products. Within that system, Poland and Romania are major exporters of cereals and animal products, Hungary exports feed grains, meat and processed foods, and Czechia plays a strong role in sugar, beer, meat and dairy exports. Slovakia has emerged as a regional hub for nitrogen fertiliser production and distribution in Central Europe, anchored by the Duslo plant and its integration into cross-border supply chains.

Fertilisers: Agrofert at the centre of CEE’s nitrogen system

Agriculture, however, is not only about land. It depends on inputs — seeds, fertilisers, chemicals and machinery — as well as processing and logistics. Among these, fertilisers are the most strategic input, often shaping farm profitability more directly than any other single factor.

CEE’s fertiliser market is dominated by a small number of national and regional champions, with one or two firms controlling most domestic production in several countries. By revenue, Agrofert is by far the largest fertiliser-linked agribusiness group in the region, followed by Poland’s Grupa Azoty. They are trailed at some distance by Hungary’s Nitrogénművek and Romania’s Azomureș, whose market role is structurally different.

|

Country |

Champion |

|

Poland |

Grupa Azoty + Anwil |

|

Hungary |

Nitrogénművek (Bige Group) |

|

Slovakia |

Duslo (Agrofert Group) |

|

Czechia |

Agrofert Group (through its

subsidiaries) |

|

Romania |

Azomureș (Ameropa) |

Czechia stands out as an exception in production terms: it has high fertiliser consumption but limited domestic manufacturing capacity, making it structurally dependent on imports, primarily from Slovakia and Poland. That dependence is nuanced, however, because Slovakia’s main exporter, Duslo, is owned by Agrofert, a Czech-based conglomerate.

This ownership structure gives Agrofert a uniquely influential regional position. Through Duslo, the group controls a critical segment of the gas-to-ammonia chain that underpins nitrogen fertiliser economics across Central Europe. Agrofert is the only company in the region with a fully integrated, cross-border footprint, linking fertiliser production, large-scale farming and food processing — most visibly along the Slovakia–Czechia–Hungary axis.

In Poland, Grupa Azoty is the flagship fertiliser and chemicals producer and the second-largest player by revenue in the CEE fertiliser market. In Hungary, Nitrogénművek is a smaller but strategically important producer, supplying roughly 60% of domestic demand and anchoring Hungary’s position as both an importer and exporter within the regional fertiliser network.

Romania’s Azomureș occupies a different niche. While its revenues can rival or exceed those of Nitrogénművek in years of full operation, its output is far more volatile. Azomureș functions as a swing supplier: when gas prices allow full production, it dominates the Romanian market; when mothballed, Romania rapidly becomes import-dependent, amplifying price sensitivity and regional trade flows. This volatility makes Azomureș less of a stabilising anchor and more of a cyclical balancing point in the CEE fertiliser system.

Over the past five years, fertiliser markets across the Visegrád countries and Romania have been shaped by a single shock. In 2022, EU fertiliser prices more than doubled year-on-year as soaring gas prices fed directly into ammonia and urea production costs. Major producers across the region — including Grupa Azoty, Nitrogénművek and Azomureș — curtailed or suspended output.

From 2023 onwards, falling energy prices brought relief, but demand remained subdued as farmers cut application rates. Fertiliser use fell sharply in 2022 and continued to decline in 2023, while prices only gradually normalised through 2024.

Across Central and Eastern Europe, fertiliser and soil-improver producers do not formally coordinate. Instead, they display parallel behaviour shaped by shared gas costs, import competition and dense cross-border trade. As a result, prices are largely determined by global benchmarks and energy costs, while regional producers influence availability and local premia rather than acting as independent price-setters.

This is the first part of a series. The next instalments will examine processing, trade and logistics, to show where value is created — and captured — in Central and Eastern Europe’s agri-food chain.