Hungary's ‘race to the bottom’ currency policy comes under fire - CET analysis

Hungary’s currency, the forint, has in recent weeks plumbed all-time lows against the euro. Although currencies are dropping across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) due to the war in Ukraine and its resultant sanctions, the forint’s fall has been the region’s most precipitous. The fall of the forint has exposed the risk of an economic development policy that long preceded the war, and which is now being tested.

Rising inflation and currency depreciation proliferate across the western world. Their main driver has been the soaring energy prices as a result of war in Ukraine, and the retaliatory sanctions against Russia. However other factors include pandemic-related money outflows, and the respective monetary policies of the US Federal Bank and the European Central Bank (ECB).

The euro area interest rate has fallen against the dollar throughout 2020, as the Fed raised its base rate from nearly zero at the start of the year to within a range of 1.5 to 1.75%, while the ECB’s main policy interest rate remained around zero until late July, when it raised its base rate for the first time since 2011, by 0.5 percentage points. As a result, for the first time in 20 years, the euro and the US dollar reached parity.

In a crisis situation like the one caused by the war in Ukraine, investors look for a safe bay – found in the now very profitable dollar – and turn away from more risk-laden currencies that have to be converted into foreign currency in large amounts to cover energy import costs. Investors are also tending to dump euros, and the national currencies of CEE countries closest to the war zone and most exposed to imported energy.

These are the global tendencies detectable in all of the countries of the western world, but these overlap with some features particular to CEE. One of these features is the steep fall of the forint, which has exceeded those of other regional currencies.

The forint’s divergence from its CEE peers began well before the war, and economic and monetary policy measures have played a role in this, notwithstanding the impact of the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and other global trends.

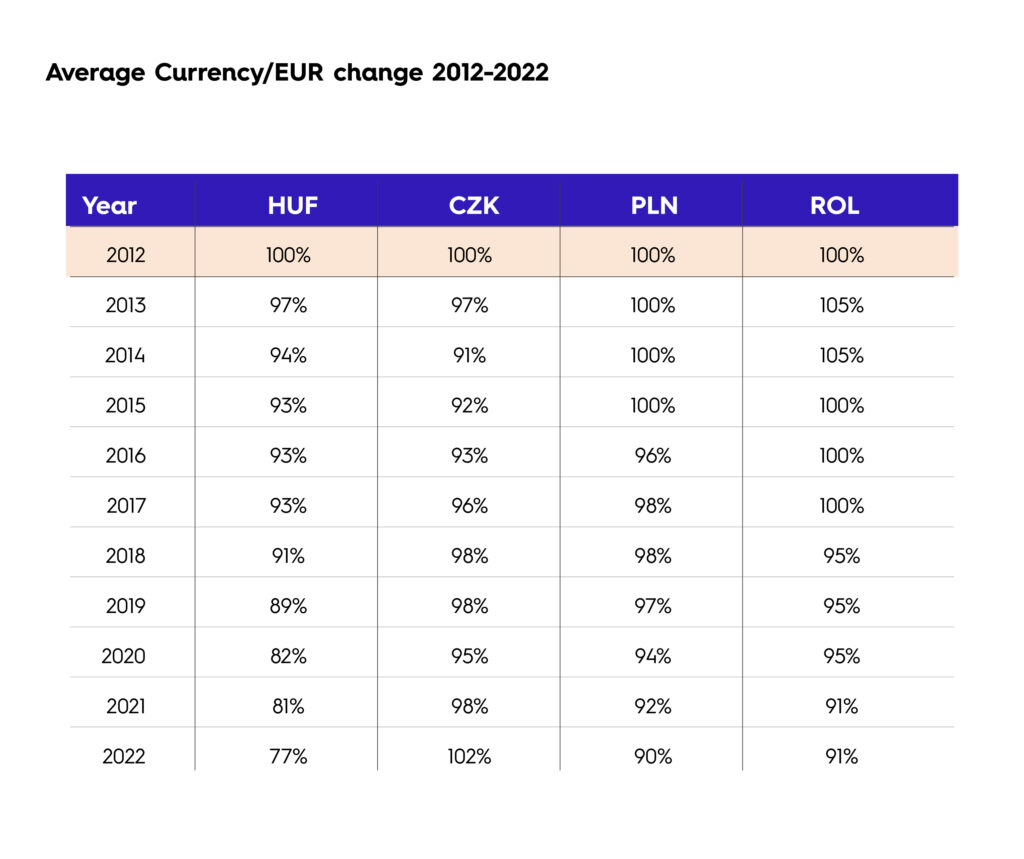

Historical data on CEE exchange rates support this claim. Over the last decade, the forint has shed 23% of its value against the euro, as compared to the Czech koruna, which strengthened slightly against the euro over the same period. Data reveals the pandemic as a fault line – in 2020 the forint dropped 7% against the euro, while other CEE currencies got off more lightly.

As former governor of the National Bank of Hungary (MNB), Gyorgy Suranyi, pointed out in a recent interview with the popular Friderikusz podcast, the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the forint over the last decade was 50%.

The forint has performed far worse against the US dollar than its regional peers over the last ten years, although all CEE currencies dropped considerably. While the Czech crown shed 18% against the greenback, compared to the Polish zloty (27%) and the Romanian leu (30%), the Hungarian forint weakened most, by 39%. The euro is down 21% against the dollar compared to 2012.

The Hungarian government mostly blames the war and sanctions for the extreme depreciation of the forint, which finally broke through the psychological barrier of 400 to the euro in July.

However, data show that the forint began its slow but inexorable slip against the euro back in 2016. Certain factors influencing the forint’s fall seem to be the consequences of a conscious economic and monetary policy on the part of Hungary.

In a previous analysis, the Central European Times examined how the war in Ukraine has dealt a harsh blow to CEE currencies. CET argued that besides CEE countries’ proximity to the war and exposure to energy imports, central bank reserves and public debt have also affected the appeal of respective currencies.

The MNB has considerably increased its financial and gold reserves over recent years, reaching over EUR 38bn in 2022, surpassing short-term external debt by over 10bn. This means Hungary had easily met the “Guidotti-Greenspan rule”, which states that a country’s reserves should equal short-term (of one-year or less maturity) external debt. Nevertheless, Hungary still has the smallest reserves in comparison to other countries in the region, and this explains why it has had to hike its interest rates, while Poland sold foreign currency on the market.

The government debt-to-GDP ratio – another important factor for exchange rates – continually fell in Hungary in the years before 2020: from 78.1% in 2012 to 65.5% in 2019. However, this figure then rose to around 79% in 2020 and is currently around 75%. By contrast, government debt-to-GDP is currently 53.3% in Poland, around 56% in Romania, and 43.3% in Czechia.

A conscious policy led to the current situation

The forint was on a steady slide even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and a closer look at the Hungarian economic and monetary policy of the last decade sheds light on this phenomenon.

As ex-MNB governor Gyorgy Suranyi recently pointed out, the forint did not weaken accidentally. The last decade has been characterised by a slow but gradual – even purposeful – currency depreciation being tolerated by Hungary’s central bank, with the latent consent of the government.

With a relatively weak forint, economic policy makers within the Hungarian government expected to boost foreign trade, FDI and GDP. By making exports cheaper, they sought to make Hungary more attractive than neighbouring countries to investors, and thus foster economic prosperity. To keep the forint low, the MNB engaged in currency purchases and converted a considerable amount of Hungary’s EU funds into forints: EUR 3-5bn per year up to 2020, according to Suranyi.

Suranyi claims that policies based on very strong or very weak currencies are both extremities as each leads to over-valuations or devaluations, and ultimately negative economic outcomes. In such a small and open economy as Hungary’s – where imports amount to 80% of GDP and are present in almost all activities and services – a plunge in exchange rate will soon affect domestic prices. Therefore, the currency rate must act as an “anchor”, Suranyi says, and should not be allowed to float as suggested by Economic Development Minister Marton Nagy who has proclaimed that “the exchange rate is exactly where it should be because it is determined by the market”.

The ex-MNB chief conceded that a weak forint has indeed boosted exports, but the aforementioned benefits cannot override the harmful effects, as Hungary’s exports and imports are not in balance.

Assuming a correlation between FDI inflow, foreign trade and consequent GDP growth, an examination of the performance of the Hungarian economy as compared to its regional peers in the last ten years is enlightening.

Trade surplus the norm in Hungary

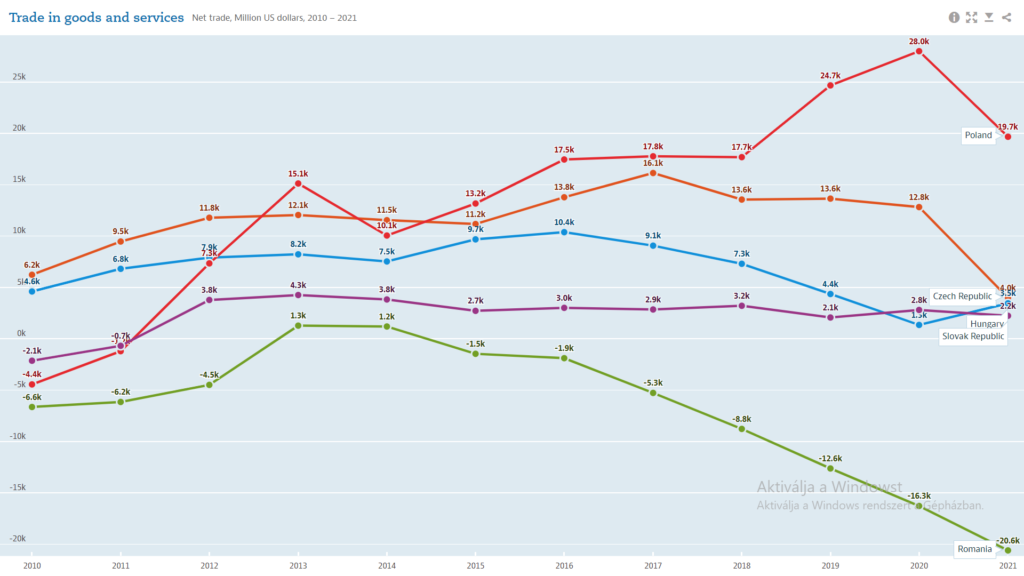

Hungary’s foreign trade took off in 2010 (having been constantly in deficit from 1992-2009) and exports kept soaring until 2016, when trade surplus was 4.6 billion euros, or 8.4% of GDP.

Contrary to Suranyi’s claim, trade surpluses have largely been the norm in the Hungarian economy in the last decade, and trade deficits were the exceptions closely related to unprecedented events.

When net trade temporarily dropped below zero in 2018, the MNB calmed concerns by saying growing investments and domestic consumption had pushed up imports, but balance would be restored as soon as those investments started to deliver.

Hungary’s trade deficit for seven consecutive months at the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022 was caused by pandemic restrictions, disruption of supply chain lines and delivery bottlenecks – notably the chip shortage – and most recently the war in Ukraine. According to the latest data, Hungary recorded a trade deficit of EUR 475mn in April 2022, and a trade surplus of EUR 135mn in May. Skyrocketing import energy prices can easily rebalance trade again – as it did in Germany, another export-driven economy.

Trade in goods and services, Poland, Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, millions US dollars, 2010-21

The fact that Hungary ranked the 34th in the world for total exports, but only 54th for economic output in 2020, according to the OECD, illustrates the extent to which the Hungarian economy has become export-driven. In terms of exports to GDP ratio, Hungary was in the top 12 in the world in 2020.

Nevertheless, the Hungarian performance was not outstanding in the region, as net exports were positive and trade surplus grew throughout CEE in the last decade, with Poland performing exceptionally well, cutting an annual deficit of USD 4.44bn in 2010 to a surplus of USD 28bn by 2020.

Hungary inarguably placed a bet on investments, and its success in luring foreign investment is hard to question or overestimate. The numbers speak for themselves:

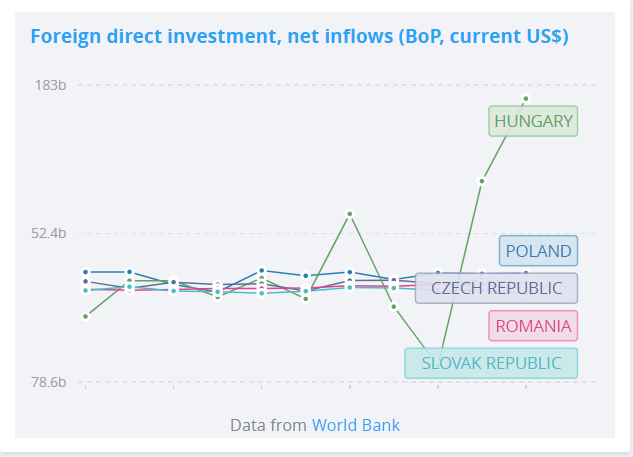

Foreign direct investment, Poland, Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, net inflows 2010-21 (balance of payments, US dollars)

The gap between Hungary and other countries is massive: Hungary attracted more than five times more investments in 2020 than Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Romania, Slovenia and Estonia combined: USD 171.37bn. In fact, this is more than Germany (USD 142.78bn), and exceeded the country’s GDP by 9%. Hungary was second only to the Cayman Islands in terms of FDI inflows in relation to GDP, and in terms of sheer value only the US and China lured more investments than Hungary in 2020.

The pandemic-related economic downturn induced Hungarian policy makers to further increase FDI inflows and speed up economic recovery. The weak forint was of course not the only factor in Hungary’s appeal to investors: outstandingly low corporate tax (9%) and tax breaks were also major draws. Despite wages growing by double digits in Hungary, their foreign currency value kept them under control, favouring foreign investors. Indeed, unit labour costs in Hungary were the third lowest in the EU last year.

As a result, investments expanded in Hungary by over 12% in 2021, as the unemployment rate fell below 4%, and economic output grew by 6.1%, one of the highest in Europe. In 2021, Hungary’s GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity grew from 74% to 76%, which was the highest in the Visegrad Four. Based on GDP per capita on purchasing power parities, Hungary overtook Portugal last year, was trailed by Romania, Latvia, Croatia, and Slovakia, but was behind Poland, Czechia and Estonia.

Will FDI pay off for Hungary long term?

Until the spring of 2020, the MNB consciously and purposefully damaged the forint exchange rate, Suranyi said. Since then, however, the forint’s slide has no longer been purposeful, and investors no longer believe that the central bank and the government are committed to exchange rate stability. Suranyi warned that this brand of policy can lead to “self-fulfilling prophecy”.

In the background is the dispute between the Hungarian government and the EU which has led to the freezing of recovery funds for Hungary. This has significantly impacted the exchange rate, and if an agreement is reached, the forint would recover significantly.

In this analysis, CET found that the weak forint reveals a development policy with all its benefits and risks sometimes described as “a race to the bottom”. It was US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen who once said when arguing for a global minimum tax: “We’ve had a global race to the bottom in corporate taxation and we hope to put an end to that.” Put simply, this is a sort of development strategy when a country lures investment by keeping taxes and wages low. A weak – or even pegged – currency could be viewed as integral to this approach, which is far from being unorthodox, as huge economies including China also employ it.

This development strategy is now facing a hard test in the midst of an enormous, worldwide energy and economic crisis, and the forint is suffering. Even the Hungarian economy’s high energy demand and consequent vulnerability is partly a result of this policy, as investments have mainly been in industry, which has higher energy demands than services.

Time will tell whether the huge investments of recent years will help Hungary to recover from the current crisis, or whether the unstable currency rate, rising inflation, high exposure to import energy and the war in Ukraine will deepen the crisis in Hungary, even more than for its CEE neighbours.