War in Ukraine deals harsh blow to CEE currencies

While the Hungarian forint was hardest hit, all the currencies of the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region are suffering adverse effects as a result of the war in Ukraine. Proximity to the war zone, dependence on Russian gas and the impact of EU sanctions combined to commence the CEE currencies’ respective slides, which their central banks are frantically moving to halt.

The Hungarian forint suffered the steepest decline against the US dollar (nearly 13%) and the euro (9%) this month amongst the CE4 countries (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania). Meanwhile the Polish zloty shed around 11.5% to the US dollar and 7% to the euro, slumping to its lowest value to the latter currency since 2009.

The Romanian lei got off most lightly, weakening 4.6% against the dollar and holding its value against the euro. As euro itself has dropped by around 4.5% against since the beginning of February, the disparity between the forint and the lei was three-fold. Even the Ukrainian hryvnia has managed to fare better than the Hungarian forint, analysts noted.

Hungary more at risk of currency devaluation

With Hungary’s parliamentary elections scheduled for 3 April – politicians and public figures moved quickly to give their interpretations of the slump. The government of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban blamed “reckless hints” about sanctions possibly being extended to the energy sector. Hungarian Finance Minister Mihaly Varga went further, explicitly calling the forint a victim of EU sanctions, adding that the mooted energy-sector sanction extension is “currently the greatest threat to the forint and the Hungarian people”. Pro-government media and ruling party politicians also echoed the ruling Fidesz party’s line that “those who want to extend sanctions want to make the Hungarian people pay the price of war”.

Peter Akos Bod, a member of the “team of experts” of United Opposition prime ministerial candidate Peter Marki-Zay, tweeted that Varga’s argument “echoes Moscow”. Bod added that sanctions hurt both the target and executors of sanctions, and harsh measures only make sense if the instigators sound determined and united in avoidance of worse options.

Geography, energy dependence, affect currency fluctuations

It is a matter of fact that Hungary borders Ukraine and has a pronounced dependence on Russian energy. On the other hand, Romania is the least dependent CE4 country regarding Russian gas: its government recently declared that it could easily manage without Russian fossil fuels. Moreover, investors tend to shift from more vulnerable currencies to safer ones. The conflict could also reduce capital inflows, putting further pressure on the exchange rates across the region. However, analysts have noted that the National Bank of Hungary (MNB) did not communicate as openly about its moves as its Polish and Czech peers, claiming that raising the base rate had only been a secondary cause for the sell-off. Nevertheless the MNB raised its key policy interest rate by three-quarters of a percentage point on the 3 March, its largest hike since 2008.

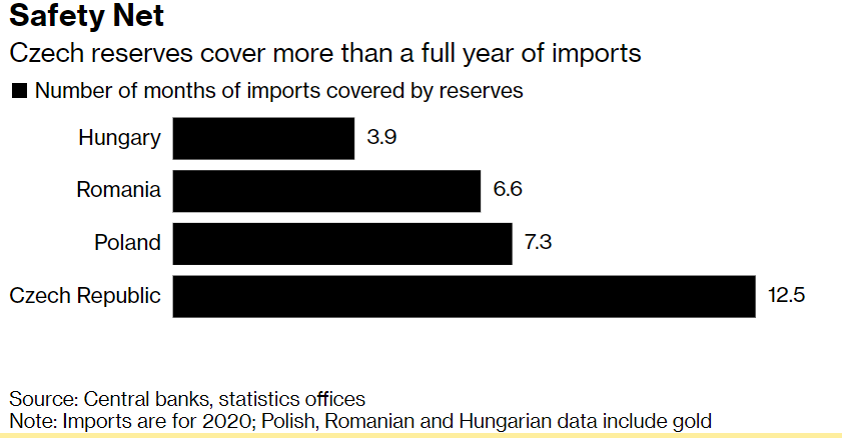

Commenting on the forint’s freefall, David Nemeth of K&H bank noted that the MNB holds the smallest foreign-currency reserves in the region, while Czechia has by far the highest amount, and Poland’s reserves also significantly exceed those of Hungary. This explains why Hungary had to hike its interest rates, while Poland sold foreign currency on the market, Nemeth added.

Forex reserves mean Poland less exposed than Hungary

The National Bank of Poland declared on 1 March that it “has an adequate level of foreign exchange reserves and has at its disposal an appropriate set of instruments to counteract negative trends in the financial and currency markets”. On the other hand, Hungary is not likely to use forex reserves for intervention as this would increase the country’s external vulnerability in the uncertain global environment. Hungary’s international reserves were €35.5bn at the end of January, of which €4.9bn was in gold while forex reserves totalled €27.9bn (around 18% of GDP).

Hungary is dependent on Russia for gas imports and nuclear energy, which renders market players especially careful. Hungarian government officials happily reported that there would be no energy-related sanctions, which they said would lead to an energy crisis in the country, after an extraordinary EU summit at Versailles, near Paris, last week. Hungary will keep retail energy prices low, as this has been a key component of Orban’s campaign ahead of the 3 April election. Hungarian households pay the second lowest gas and electricity prices in Europe in nominal terms, after Bulgaria, although when adjusted to purchasing power, Hungary prices are mid-ranking.

Facing elections in three weeks, Orban looks to get over the line

The weak forint is bad news for Orban, currently seeking a fourth consecutive term in office, as it gives ammunition to the opposition regarding the government’s economic policies. In response, the Orban government announced on Monday, 7 March that an action plan will be drawn up to preserve the stability of the economy and the exchange rate, after Orban met MNB governor Gyorgy Matolcsy. Now analysts expect the MNB to take extraordinary measures, and predict an interest rate increase of between 1 and 2 percentage points.

Poland and Czechia’s central banks have also intervened to slow their respective currencies’ slides against the euro and dollar. According to some forecasts, policy interest rates in the region may reach 6 or 7% by the middle of the year. As a swift end to the war in Ukraine looks unlikely, the sell-offs will probably continue in the weeks and months ahead.