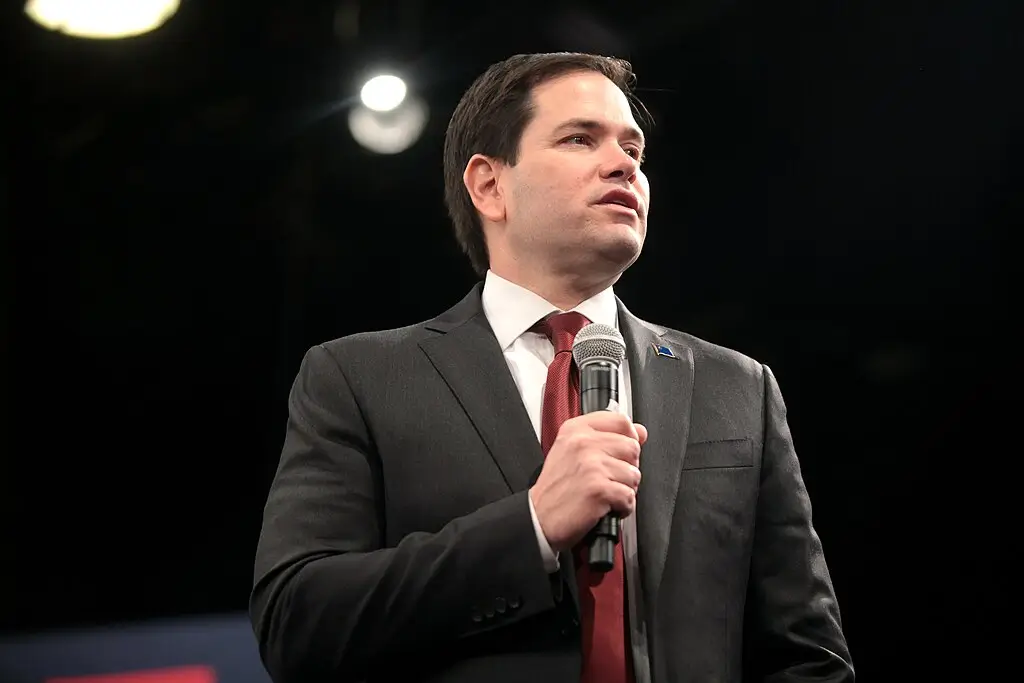

Rubio’s regional tour: Who was the U.S. signalling — and what?

Following the U.S. Secretary of State’s partial regional tour, at least as many questions remain as the trip itself answered. Analysts are trying to decipher the real message of the visits from indirect signals.

In February 2026, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio launched his mini–Central European tour from the Munich Security Conference. He paid a lightning visit to Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico in Bratislava, then headed to Budapest, where he held talks with Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó and Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Equally noteworthy is where he did not go. He did not visit Warsaw, Prague, or Bucharest — that is, other NATO allies in the region. That in itself carries message value.

Energy security was a central topic of the talks, as both Slovakia and Hungary remain significantly dependent on Russian fossil fuels, while the EU is advocating for a gradual phase-out of Russian gas imports.

NATO commitments and the peace process in Ukraine were also discussed.

Before departing, Rubio stated: “These are countries that maintain very strong relations with us, that are very cooperative with the United States,” adding that this was his first visit to these countries.

In Budapest, Rubio repeatedly and at length spoke about the advantages of the strong personal relationship between Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán, and described Orbán’s international role as indispensable. However, he did not give a clear answer to a question central to Hungarian domestic politics: for how long this relationship secures Hungary an exemption from sanctions affecting Russian energy purchases. Perhaps not coincidentally, all this occurred just a few months before Hungary’s parliamentary elections.

A Member of the European Parliament speaking anonymously was quoted by Politico as saying: “Marco Rubio speaks in a conciliatory tone, and then travels to Hungary and Slovakia. What kind of message does that send?”

Because of its partly inconsistent overt and implicit messages, the visit has generated competing interpretations.

One reading sees the tour primarily as a geopolitical signal: Washington is reinforcing ties with those EU member states that align more closely with Trump’s foreign policy vision — a swift end to the war in Ukraine, a pragmatic handling of dependence on Russian energy, and a migration-restrictive policy stance.

Another interpretation suggests a domestic political dimension: Trump is openly supporting Orbán ahead of the upcoming parliamentary elections, having previously praised him as a “strong and decisive leader.”

A visit at this timing is difficult to separate from the campaign context.

A third angle relates to the Ukrainian peace process: Hungary and Slovakia both maintain positions closer to Moscow than the EU average — which could allow them to play a mediating role, or at least weaken internal EU unity in the event of a potential agreement.

The tour simultaneously represented traditional diplomacy (energy issues, NATO), political signalling (these are Washington’s friends in Europe), and — at least in terms of timing — something difficult to disentangle from Hungary’s election campaign. As for which element was the “real” objective, it was likely all three at once — in diplomacy, there is rarely a single motive.