Forint tumbles after Moody's downgrade

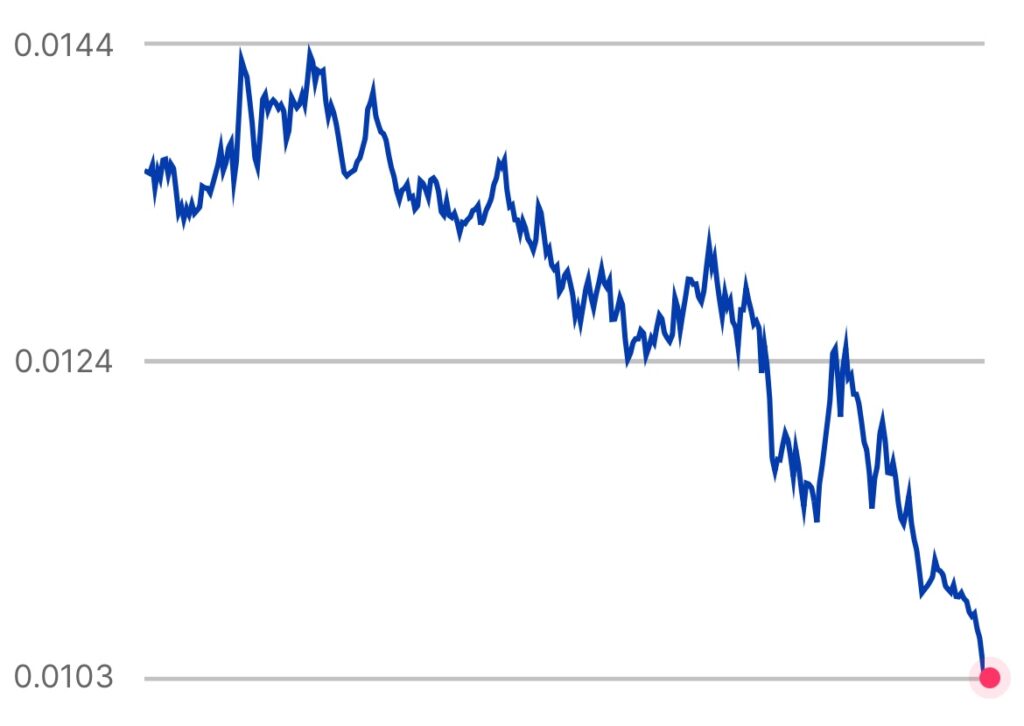

The Hungarian forint plummeted to a near-historic low against sterling on Monday morning, with a British pound buying HUF 501.5.

For Hungary, heavily reliant on imports, the forint’s fall inflates the cost of goods. When coupled with high interest rates, this inflation creates a precarious economic environment.

The euro-forint rate was also bad news for the Hungarian currency, as a euro bought HUF 415.05 on Monday 2 December, a 2-year low.

Moody’s downgrade hits forint

Last Friday Moody’s Investors Service downgraded Hungary’s outlook from stable to negative, citing a combination of external and domestic risks.

Although the credit rating agency reaffirmed Hungary’s investment-grade credit rating at Baa2, the decision also reflected growing concerns about the country’s disputes with the EU over governance and rule-of-law issues, as well as broader economic vulnerabilities.

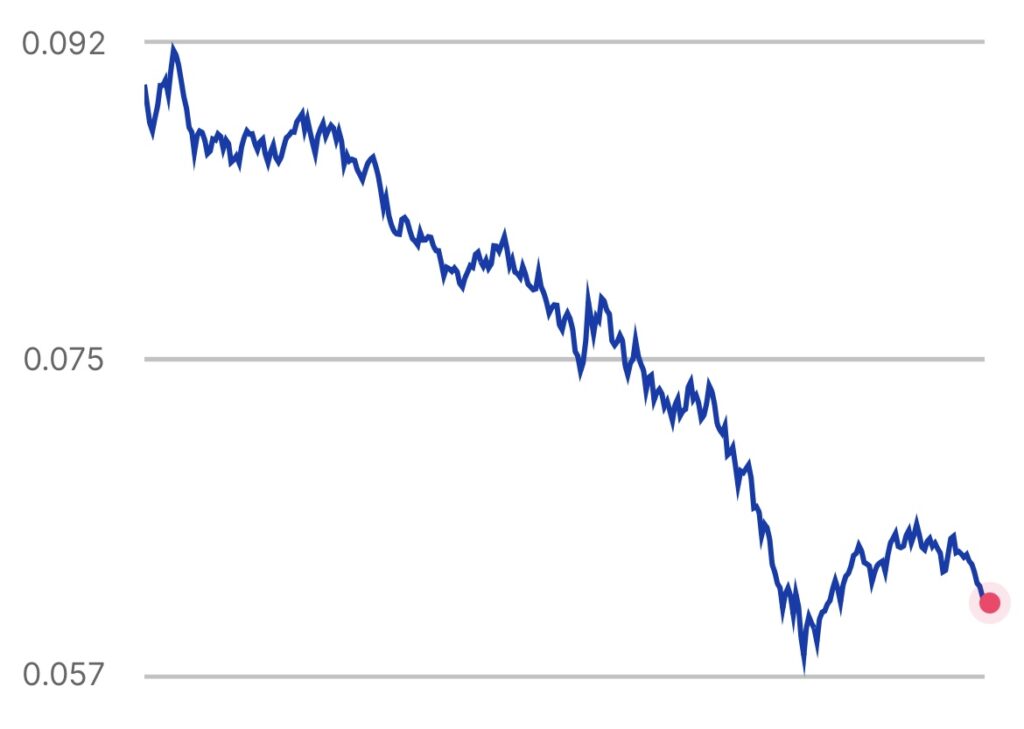

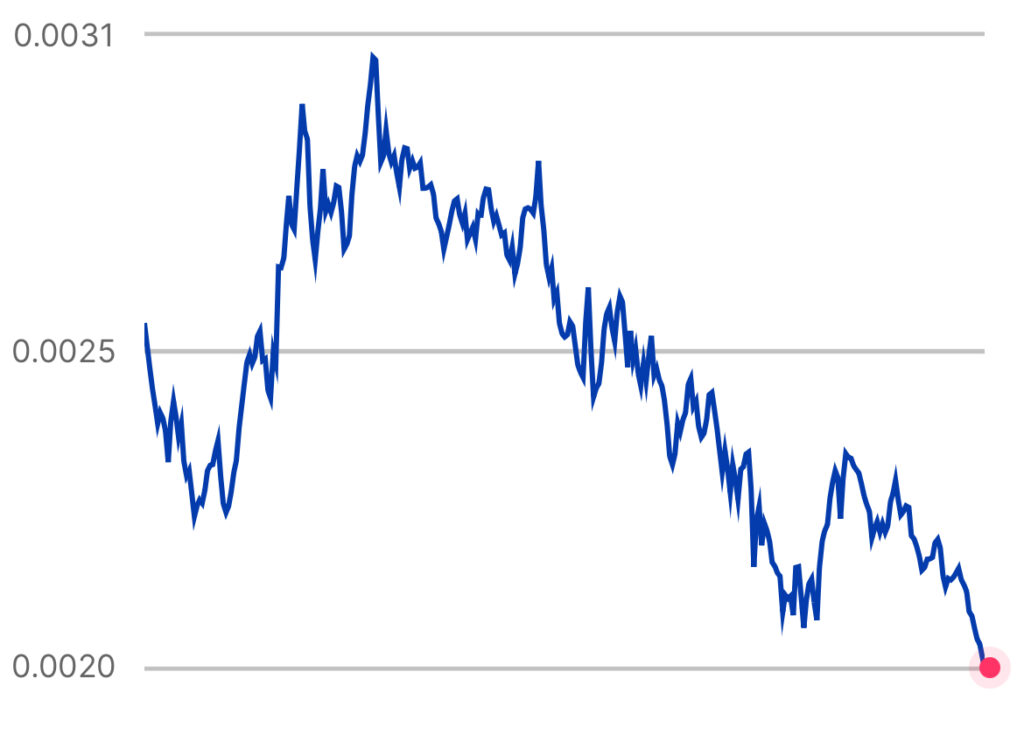

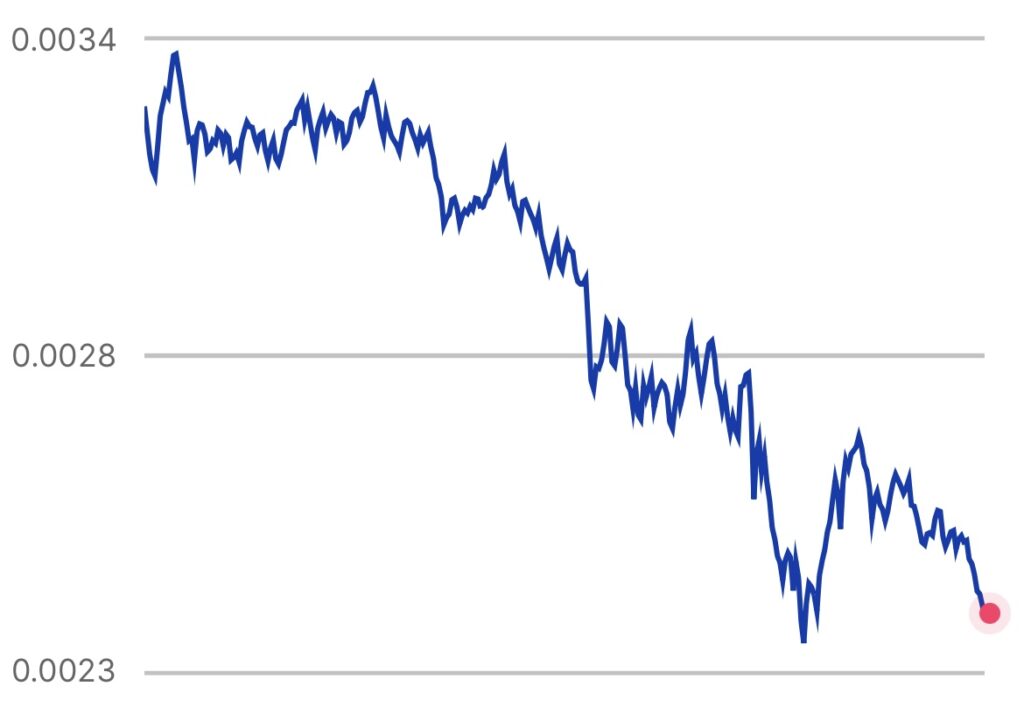

The forint is also performing poorly against the Polish zloty and the Czech koruna, Hungarian business weekly Vilaggazdasag noted, however.

The Hungarian Economy Ministry responded to Moody’s downgrade by affirming Hungary’s economic resilience, pointing to successful securities auctions, the 2025 deficit-cutting budget aimed at driving GDP growth above 3%, and positive trends in retail sales, tourism, and employment.

Moreover, Hungary continues to attract significant foreign direct investment (FDI), notably from Chinese electronic vehicle battery maker CATL and carmaker BYD. The government also underscores strong investor confidence, evidenced by. These factors, alongside positive macroeconomic indicators, support the country’s broader narrative of economic stability.

Nevertheless, weak demand from key European markets, particularly Germany, has hit exports, tempering optimism. Hungary is also still navigating the economic fallout from the COVID:19 pandemic, compounded by the energy crisis and the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Moody’s decision serves as a reminder of Hungary’s vulnerabilities that will require fiscal reforms, efforts to reduce inflation and debt, and maintaining high employment. For now, Hungary’s ability to navigate these challenges will determine whether it can maintain investor confidence and return to a stable outlook.

The downgrade reflects concerns over Hungary’s governance and its potential loss of EU funds, exacerbating fears about the country’s fiscal stability. Simultaneously, global market trends have added to the pressure, with the US dollar gaining strength.

Economist Viktor Zsiday told local media that Hungary’s current interest rate policies are insufficient to stabilise the forint, adding that recent rate cuts aimed at stimulating growth have inadvertently fuelled its slide.

He suggested two possible routes forward to stabilise the forint: raising rates to attract investors or continued rate cuts, risking further depreciation and heightened inflation. Ultimately, investor fears lie in Hungary’s economic policies and political risks, which only the government can address, Zsiday underlined, however. Without these, stabilising the forint may remain a distant goal.