EU plan to source local raw materials will boost mining, battery industries in CEE - CET analysis

The EU’s mooted ‘critical raw materials (CRM) law’ would strengthen the EU’s autonomy by reducing its reliance on third countries for the supply of essential minerals for green energy and modern industry. Proposed recently by the European Commission (EC), the legislation would mean the reopening of mines earlier deemed unprofitable and a spike in clean energy projects such as gigabattery plants in Europe.

Strategic autonomy is increasingly high on the agenda for myriad reasons, so much so that the doctrine has been formally adopted by the European Parliament. One reason is the EU’s precarious dependence on countries outside the bloc for materials such as lithium, magnesium and cobalt, which are critical to its digital economy and clean energy transition plans. The EC’s proposal is thus designed to bolster European clean energy projects, for example battery plants.

The CRM bill issued on 16 March identifies 34 ‘critical materials’, 16 of which are also ‘strategic raw materials’. “To ensure the EU’s access to a secure, diverse, affordable and sustainable supply of critical raw materials”, the EC proposed strengthening ties with reliable trading partners, enhancing recycling, and ramping up mining inside the European trading bloc.

According to plans, no single third country should contribute to over 65% of the EU’s annual consumption of a strategic raw material at any stage in its processing. By 2030 the EU is aiming to extract a minimum of 10% of its annual consumption, process a minimum of 40%, and recycle at least 15%.

The plan will likely require a reconciliation of mining projects with environmental and social standards, as the EU is considering prioritising projects of vital public interest over conservation laws.

Some EU lawmakers believe Europe cannot increase mineral supplies without easing strict environmental regulations that make opening new mines difficult. However, the EU does not consider CRM self-sufficiency to be achievable. Instead, besides ramping up domestic mining, the plan aims to diversify procurement and strengthen ties with reliable partners.

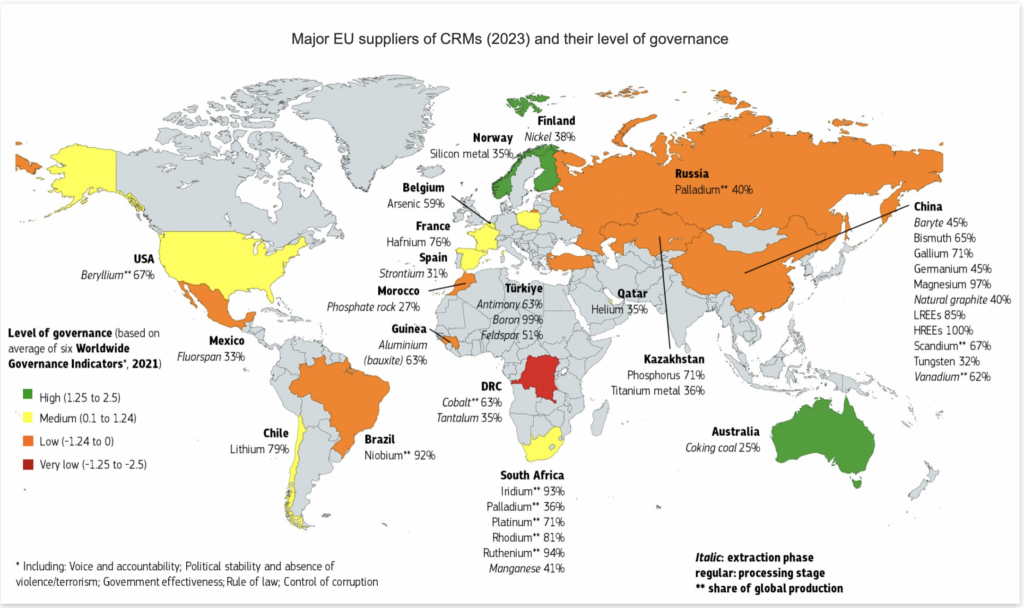

The EC defines “reliable” as countries with a high level of governance. Cobalt, for example, is most commonly imported from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), but the African country has a poor record on human rights and child labour. Nonetheless, the EU currently imports most of its critical raw materials from China, Russia, Brazil and the DRC, with them often providing over 90% of its supply.

CRMs are vital for the European economy and, in some cases, their supply is at risk. Lithium and cobalt, for example, are in high demand in the sectors of electric vehicle batteries and energy storage. To meet projected industry demand, the EU would need up to 18 times more lithium and 5 times more cobalt by 2030. By 2050, demand for lithium is expected to have increased by around 6,000%, and by 1,500% for cobalt.

The EU is now considering potential CRM deposits and projects in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). These could play a significant role in supporting major clean energy and battery projects in the region, but also stir up heated social debate about local conservation areas and long-term EU policy goals on strategic autonomy and emission targets.

Lithium – the new oil?

That lithium is now referred to as “white gold” illustrates its importance as a strategic raw material. Some expect the metal will become similar to oil in the past, meaning it will determine geopolitics and even armed conflicts. Countries with significant lithium deposits will benefit from increased power and wealth, much like the OPEC countries today.

As a key ingredient in battery making, lithium is central to electric vehicle production. The soft, silvery-white alkali metal is also used to produce heat-resistant glass, ceramics, and psychiatric medicines.

Chile supplies most of the EU’s lithium, with the US and Russia also major exporters to the bloc. South American countries are already looking at forming the new “Lithium OPEC”. Argentina, Chile and Bolivia, the so-called ‘lithium triangle’, contain about 65% of the world’s known resources of lithium, and collectively reached 29.5% of world production in 2020. Along with Brazil, these countries are now considering creating a lithium cartel to expand South America’s processing capacity, turning more of their mined lithium into batteries. This development underlines why the EU needs to have lithium excavation on its own soil and prevent over-reliance on external sources.

The EU does have the potential to source lithium inside its own borders, in countries including Portugal, Czechia and Spain. However, most project plans have met with strong opposition at the local level.

The Czech lithium deposit is especially important because it is now considered the largest in Europe. In 2017, Czech state enterprise Diamo and the national geological service joined forces to develop a methodology for evaluating CRMs and boost the exploration of new raw material deposits. They raised the possibility of opening a lithium mine in the Ore Mountains, Cinovec, located 100 km from Prague, close to end-user car makers and companies involved in energy storage.

The project is now being carried out by European Metals Holding in a joint venture with the energy trade conglomerate CEZ. The enterprise aims to annually produce nearly 30,000 metric tons of battery-grade lithium for 25 years. Moreover, Cinovec could become the lowest-cost hard rock lithium producer in the world, according to European Metals’ 2022 feasibility study.

Rare elements unearthed in Sweden, Romania

Demand for rare earth elements (REE) could increase tenfold by 2050. Used in permanent magnets in electric vehicles, digital technologies and wind generators, they are imported almost exclusively from China. Despite REE deposits in Sweden, Greenland, Finland and Spain, they are currently not mined in Europe at all.

In January, Europe’s largest-known REE deposit was discovered in northern Sweden, although it could take 10-15 years for extraction to commence. Another recent discovery occurred at the Ditrau complex, in Harghita county, north-east Romania, where an alkaline layered intrusion with high levels of REEs and niobium, a rare earth metal, was unearthed.

REEs could also be extracted as a by-product of phosphate production, notably in Finland, and recycled from end-of-life products. The resource- and cost-effective design of magnetic materials and motors also holds enormous innovation potential.

EU could pivot to Romania, Bosnia for magnesium

Magnesium – a key alloying element found in minerals and saltwater – is used to make steel and aluminium in a variety of industries including transport, space, consumer electronics and laptops and pharmaceuticals. The EU imports 93% of its magnesium from China, the world’s largest producer of the metal.

In 2021, magnesium prices skyrocketed after China restricted its power consumption, leading to the underutilization of the output capacity of its smelters, and a sharp decline in magnesium production. As a result, Europe’s automotive, construction and packaging sectors faced serious challenges.

Low production costs in China make it almost impossible for European magnesium smelters to be profitable. Europe’s last smelters closed in 2001, and the EU has only small known deposits of the metal. Since the EC named magnesium a priority critical mineral, two companies in Romania and one in Bosnia and Hercegovina have been gearing up to restart production of the metal.

Cobalt vital ingredient for phones, vehicles

Cobalt – in bygone days used mainly to make blue pigment – is now a major component of rechargeable batteries for smartphones and electric cars. As a result, the blue metal is expected to play a key role in digital and green energy industries, as demand grows significantly over the next decade. The metal is also used to make aircraft turbines heat-resistant.

Over 80% of the EU’s cobalt is currently imported – over 50% from the DRC – with Finland and French Guiana also providing the metal. Although Poland has cobalt-containing Kupferschiefer-area deposits, their cobalt grade is relatively low (0.005–0.008%) and it is currently not economical to exploit without any significant improvement in extraction technology.

However, in Bihor, western Romania, Canada’s Leading Edge Materials Corp (LEM) last year endeavoured to reopen a nickel and cobalt mine together with a Romanian state-owned metal prospector and mine-management service provider Radioactiv Mineral Magurele. LEM recently announced the project was ahead of schedule and commenced reopening old galleries within the Bihor Sud nickel and cobalt exploration site.

Platinum found in Poland, Serbia, Finland

Platinum is a key ingredient in catalytic converters and is likewise used in a variety of industries from TVs and car airbags to pacemakers.

As there is no domestic production of platinum in the EU, all of its supply of the precious metal is imported at present, mainly from South Africa, Russia and the US.

Copper ores with platinum content are now being sourced at ZG Lubin Zachodni and ZG Polkowice Wschodnie mines, in Lower Silesia, Poland. Meanwhile, promising platinum explorations are underway in Serbia and Finland.

Mining is expensive and could prove even more so in Europe, where environmental standards are tightly regulated. Nevertheless, over-reliance on countries such as China and Russia could prove even more costly in the long run and put entire industries at risk. This became clear during the Coronavirus pandemic, when global supply chains were disrupted, and even more so when Western sanctions cut many ties with Russia.

European Commissioner Thierry Breton, therefore, has urged European financiers to provide more funding to suppliers of critical minerals. Breton also warned that the EU is already lagging behind the US and Canada, where laws have already been passed to secure clean energy and essential energy-transition materials.