How to get the robots “out of the cages” - developing robotization in CEE

A professor at Hungary’s Matthias Corvinus Collegium (MCC), these days Zoltán Cséfalvay studies robotization. Of his current teaching and research there, he offers: “We are dealing with the economic issues, the technological part of the industrial revolution, what impacts it has on society and employment, and on geopolitics as well. My lectures try to put all of these aspects together.”

Cséfalvay certainly has an interesting resume. Having worked as a State Secretary for Economic Strategy at the Hungarian Ministry of National Economy, he served in diplomatic posts at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in Paris, until his recent return to Hungary from a research position at the European Commission’s Research Unit for Innovation in Seville, Spain, where he focused on robotization.

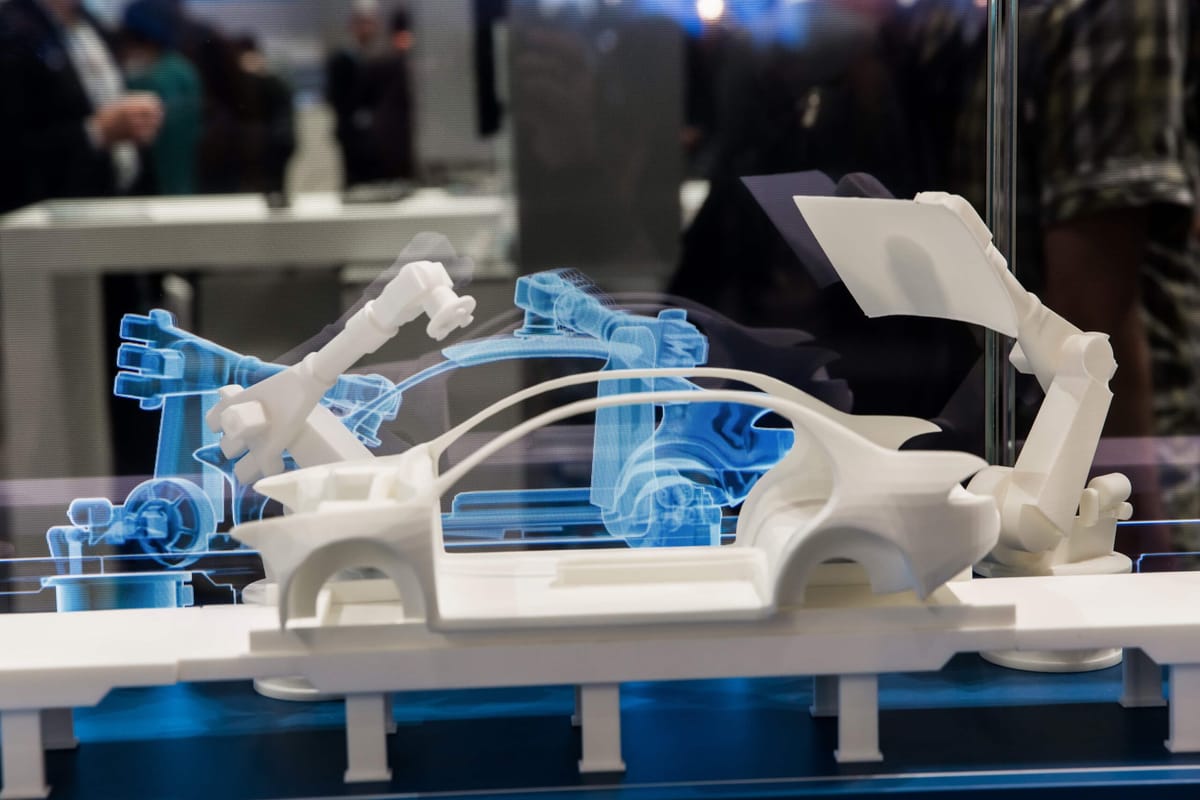

These days, at the Center for Next Technological Futures at MCC, one of the research projects he is currently working on is called “Moving Robots Out of the Cages,” which focuses on the shift from ‘industrial’ robots to ‘service’ robots.

In reference to his recent research paper on that very subject, Professor Cséfalvay spoke to Central European Times about the trajectories of and prospects for robotization in Central & Eastern Europe (CEE). He began by differentiating between the ‘caged’ robots – industrial robots for particular industrial tasks, already being used extensively in the region – and the ‘uncaged’ kind: service and collaborative robots that are still in a nascent stage of development but which could be a promising area for the region, if steps are taken to push them forward.

ZCS: At present, service and collaborative robots are quite the opposite of industrial robots, as the latter are deployed on a large scale, but used in only a few industries. Service and collaborative robots are currently only being developed on a very small scale: globally, the annual sale of industrial robots is about 400k or more, while they sell 100k service robots, which are deployed in an ever wider range of application areas.

It’s a simple story of automation: industrial robots are stupid – they are not intelligent anyway. They have nothing to do with the robot movies and what we expect for how intelligent they are. Welding robots in a car factory work in protective cages, that’s why I called this whole story “robots in the cages.” They’re pre programmed machines, part of the long story that we’ve had in the last 200 years. They are better than previous machines and their impact on employment, society is similar: robotization has increased productivity, and certainly it has influenced employment.

For the latter, we’re currently in the discovery phase. Sometimes they’re used in restaurants and hotels, in hospitals, also in defense or construction. The range of application areas is broadening. Because these robots are not in the cages, they can be used in those environments where we as humans can’t do the activity – drones, for example – because we can’t fly! But there are also those that go underwater in search of a diamond as in the Titanic movie – these are applications which are obvious things robots can do better and that’s really the point at which countries in CEE could join in. That means more investment into robotics development, working together with universities and robot manufacturing are all part of the story.

CET: So how much of a phenomenon are industrial robots in our region?

When you look at the Hungarian figures, we currently have around 9,000 industrial robots, but when you see in time how this developed you find the clear connection when these car manufacturers – Audi, Mercedes – doubled their production and opened a new line, which meant they needed more robots, and this increased the number of industrial robots in Hungary – so there’s a strong connection to that.

The strange thing is that they are deployed on a large scale – currently, around the globe there are 2.8 million industrial robots and the majority, more than 700,000, are in China, which is currently the biggest deployer of industrial robots, and the remainder are in the US, EU, Korea and Japan, all of which have around 90% of all industrial robots in the world – so it’s very concentrated.

How do labor costs figure into their deployment?

Interestingly, high labor costs drive robotization. In those countries where labor costs are relatively low, and in those industries – textiles and other – robotization is also very low.

At first sight, it’s a little surprising that you don’t have industrial robots in industries where you’d think it would be relatively easy to automate. There aren’t any, for example, in the textile industry. They are present in the industries where the wages are relatively high. Though, it’s simple economics: when you look at your investment, the margin is relatively thin between costs of the robots and the costs of labor; when the margin is big, you don’t buy robots. Their average cost can be USD 80-100,000, which can be compared to two workers doing the same thing and their wages. In Germany if you purchase robots, after half a year your investment has paid off and the robots are working and working.

When we see Central & Eastern Europe, that’s one aspect which could be a bit of a burden for further robotization – relatively low labor costs. On the other hand, because these countries in CEE – Poland, Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary – are very strongly specialized in those industries where robots are part of the normal procedure, it means they are relatively well positioned in robotization. In other words, what really drives robotization in these countries is their specialization in the so-called robotized industries – that’s why they have a high number.

What other factors determine the rate of robotization in CEE?

There’s a bit of a dependency and risk in that in CEE the deployment of industrial robots depends on the decisions of external investors. That means that while the current number in Hungary is 9,000, when BMW will build its factory in Debrecen it will deploy more than 1,000 robots, so the overall number will decrease – but this doesn’t come from our economy; it emanates from the decisions of others.

Secondly, when we’re talking about industrial robots, we should look at the whole value chain, because the robots should be developed, through research and then manufactured and, following that, they’ll be sold and deployed at the robot user manufacturers, which means, for instance, the carmakers. When you look at this chain you can see where the value added is: robotics development, manufacturing and, certainly, when you go through the chain, at the deployment of the robots there’s no such high added value – certainly in the production there’s high productivity, more precise work and so on.

How could these countries push the robotization chain forward?

They’d need to delve into robotics development much more deeply than currently, and get into robot manufacturing. Europe is actually very capable in robot manufacturing, and when we look at the entire chain, we can see China has currently the highest number of industrial robots deployed, but on the other hand, China is lagging far far behind when we look at robotics development and manufacturing of robots, according to our calculation based on the number of patents. Europe, Korea and Japan are very strong in robot manufacturing, and the US is certainly very strong in robotics development.

For Central & Eastern Europe I think it will be vital to move to this more value-added part of the robotization chain. There’s a very interesting aspect about which we don’t yet have much data, and that’s “reshoring” or “homeshoring” of production. Theoretically, robotized production makes it possible for those activities or production which were outsourced during the past two decades of globalization, to China, Vietnam and Indonesia, to come back – in theory. From the point of technology, robotization would enable this kind of shift back.

“It’s a simple story of automation: industrial robots are stupid – they are not intelligent anyway. They have nothing to do with the robot movies and what we expect for how intelligent they are. Welding robots in a car factory work in protective cages, that’s why I called this whole story “robots in the cages.” They’re pre programmed machines, part of the long story that we’ve had in the last 200 years.”

We’ve been talking mostly about industrial robots, but in terms of AI how do the low costs of data programming fit into potential advantages for the CEE region?

We have very real chances. It’s a shift that we are now in, to move towards service and collaborative robots. Whether you like it or not, the whole issue of industrial robots is dominated by large countries and large companies. They are designed for large, mass production. By contrast, the service and collaborative robots – when you are working alongside robots – it opens up a way for smaller countries as the use of these robots is increasingly locally embedded.

So, as we move forward in this story about service and collaborative robots, our figures show that the competition globally is more diverse – not just the big five countries: China, EU, US, Japan, and Korea, but also the UK, Israel, Singapore, Canada. It’s more diverse, and the chances for smaller countries, when they specialize for some part of the service or on collaborative robots, are greater. With service robots you have to decide what sort of specialization – they are used in small-scale production, which means you have to design and modify the robots to the requirement of the special plans or companies, and that’s where we in CEE have good prospects.

In one of your papers, you mention the lack of venture capital opportunities in the region. How much of a hurdle is that? It seems much more difficult here than in some places.

Venture capital has a role in this new story; in the old story of the classic automation dominated by large companies, it’s not needed. These car manufacturers buy the industrial robots, have in-house robot development, and they deploy them.

In the story of the service and collaborative robots, we are now in the discovery phase, discovering how we can use them and developing new types of robots – that’s where large companies and the small start-ups have a role, so that’s where they have a market niche and when they have that venture capital invests in that, seizing the opportunity.

We shouldn’t confuse artificial intelligence and robotics – there’s a crystal clear distinction: AI is something which exists only in computers; robots are different, they’re physical. From the investment perspective, it’s better for venture capital to invest in artificial intelligence because you can scale that – when you have an application or algorithm, you can scale immediately. When you invest in robotics, it requires a huge upfront investment: machinery and so on – their results are something you can touch. It’s not so easy to scale.

What sorts of policy initiatives are coming out of Brussels that can foster this industry?

When we see the service and collaborative robots, I think the challenges are different. One is, because this kind of production is small-scale, and locally embedded, I think those EU initiatives, say smart specialization or Industry 4.0 when they’ll be more targeted to robotics, would be helpful. Second, because the start-ups play a big role, nurturing them or promoting the ecosystem would be very helpful.

Europe has a big advantage in this case because service robots can be used in the public sector, which is very strong in Europe. One could consider what robots you could use, for example, in hospitals.

“From the investment perspective, it’s better for venture capital to invest in artificial intelligence because you can scale that – when you have an application or algorithm, you can scale immediately. When you invest in robotics, it requires a huge upfront investment: machinery and so on – their results are something you can touch. It’s not so easy to scale.”

How might more industrial robots address the labor shortages we’ve heard so much about in recent times?

The labor shortage is only being seen in some occupations, and certainly using robots could address the issue. As service robots are in the initial phase, we can’t say for example in the hospitality industry we have a labor shortage and from now on, instead of waiters, we could use robots. They do exist only as experiments. It’s not like you can go to the shop and purchase them yet.

In terms of small-scale production – Industry 4.0 – there are more chances to deploy robots in production where there are some labor shortages. But currently the labor shortages in CEE and Hungary are concentrated in only some occupations; it’s not a general thing and is also a question of labor mobility.

How then would you envision the development of robotization in the region?

The best prospects in the region are for collaborative robots, which are a part of Industry 4.0. Because the CEE countries are highly industrialized there are many suppliers of the big companies and for these suppliers it is very beneficial when they use collaborative robots. Let’s see in 5 years’ time where these countries stand in terms of small-scale industrial application of robots. I wouldn’t say they’ll be forerunners, but we’ll have a very good position globally.

Drew Leifheit