CEE must better coordinate on defence - Global Peace Index founder Steve Killelea tells CET

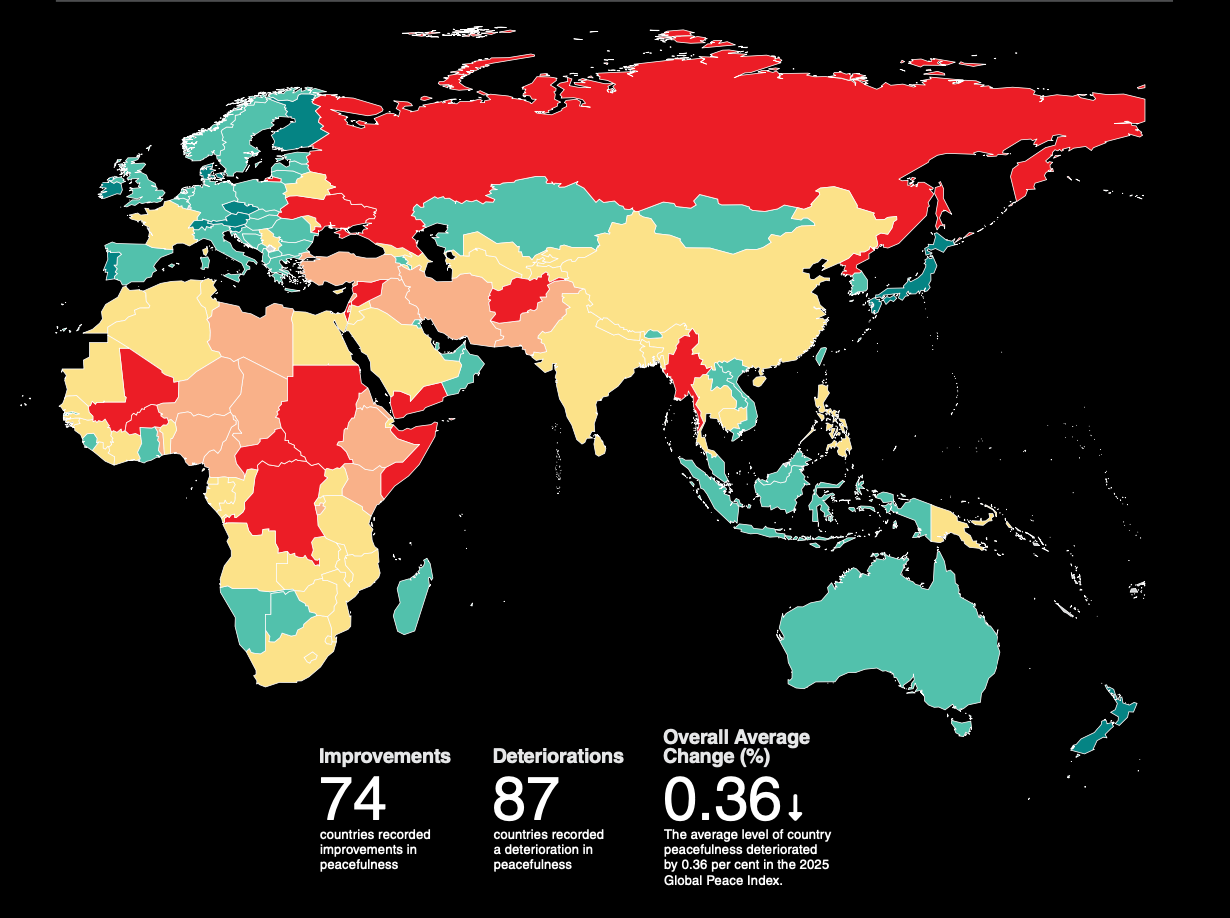

Global Peace Index (GPI) founder Steve Killelea spoke to the Central European Times about the GPI's 18th annual report. The GPI's central thesis is that peace is measurable and economically rational. Despite the steep rise in militarisation in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), investment-led ambitions are currently limited by fragmentation, Killelea tells CET.

Speaking on the release day of the Global Peace Index 2025, Killelea underlined a key finding of the new report: Europe’s strategic misalignment is its greatest vulnerability. “The real issue is not the spending on the military,” Killelea said, “it’s the integration and strategic alignment of the European countries".

EU countries spend nearly four times more on defence than Russia, but have only around one-third larger military capability, the GPI notes. While 75% of European countries increased their militarisation in 2024, Europe’s ability to field integrated, interoperable forces remains weak.

Killelea said the EU’s defence systems remain largely siloed, despite the urgency created by Russia’s land invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. He cited cases including Italy's mandating of Italian-made bullets for its weapons and Germany’s limited tank production that cannot scale beyond bespoke orders.

“There’s a lot of competition between countries building their own defence industries,” he said. “What’s needed is a realignment: the same kit... so if you do end up in a fight, it's interchangeable".

Politics complicates security convergence

Russia, for the first time, is the least peaceful country in the world on the GPI 2025. While Western and Central Europe remains the world’s most peaceful region, rising defence budgets in CEE have not yet translated into shared security, as national governments continue to prioritise domestic industries and fragmented logistics systems.

This disunity is not only structural, but also financial. Several CEE countries have launched standalone missile defence initiatives - including Poland’s Eastern Shield and Baltic regional platforms - but the economies of scale remain elusive. “Ten countries spending USD 2bn each won’t get the same capacity as one $20bn project,” Killelea said. “It’s just logical.”

EU military inefficiency is compounded by internal divergence: Romania narrowly avoided electing a Kremlin-friendly president in 2024, and Hungary remains to be seen as one of the bloc’s most Russia-aligned members.

While Killelea noted that the exclusion of one or two countries would not cripple integration, he said strategic flexibility will be required.

“You need the ability to be inclusive or exclusive,” he said. Hypothetically speaking, "if Romania pulls out, it’s not such a big deal - as long as everything else is aligned,” he added.

Militarisation can necessitate trade-offs

Slovenia ranked highest in CEE, 7th in Europe and 9th globally, despite a minor score deterioration. Czechia ranks 9th regionally and 11th globally, also slipping slightly.

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia are tightly grouped in the low 20s. Lithuania and Latvia recorded mild deteriorations, while Estonia's score increased slightly.

Lithuania rose in this year’s peace rankings despite becoming one of Europe’s most militarised states. The GPI attributes its overall gains to improved internal indicators: low crime, fewer violent protests, high political stability, and a drop in incarceration and murder rates.

“It’s a virtuous cycle,” Killelea said. “When you have strong institutions and a functioning society, that supports peace. But when militarisation crowds out health or education, the cycle can reverse.”

Slovakia and Poland followed behind the Baltic states, ranked 28th and 36th respectively, each posting moderate upward shifts in score, although Poland's militarisation trajectory continues to concern observers.

In the lower third of the table were Montenegro, Albania, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Serbia. Montenegro (34th) had the joint sharpest deterioration among CEE countries, equal to Slovenia's, while Albania, Croatia and Hungary each saw marginal increases. Hungary ranks 17th in the region but remains politically misaligned with the EU's broader strategic posture.

Moldova does not appear in this regional list, likely due to its marginal status within European data frameworks. Overall, the region remains stable in relative terms, but growing disparities in strategic orientation, defence spending and democratic resilience point to deeper fragmentation.

The report warns that countries with polarised societies or stagnant social services are vulnerable to the long-term destabilising effects of elevated military spending.

Emergence of 'middle powers' led to fragmentation

The report outlines a shift toward multipolarity, identifying what the GPI calls a "great fragmentation". Middle powers, including Czechia and Hungary, now exert influence over more than ten foreign states, up from zero in 1991. This year's GPI found that 78 countries are now involved in conflicts beyond their borders.

“These rising middle-level powers, they're not interested in lining with one camp or the other; and they're particularly interested in exerting their own influence within their own region," Killelea said, "so this is a very different dynamic". This complicates traditional alliances such as NATO and reduces predictability in global conflict mediation.

Conflict resolution fails to keep pace with escalation

Killelea warned that modern warfare is increasingly complex and difficult to win decisively, as technological advances have rendered many traditional tactics obsolete.

“Drones are changing everything,” he said. “Ukraine is producing 2.5mn this year. Future systems will navigate by terrain, not GPS, and operate in autonomous swarms. Conventional armies can’t keep up.”

The report highlights how protracted wars - in Ukraine, Syria, Sudan and elsewhere - are harder to resolve as external actors are involved, and with asymmetric tools.

The case for positive peace

The GPI 2025 reiterates its framework for “positive peace”: a systemic model that includes eight pillars from free information flows to well-functioning government and good neighbourly relations.

The eight pillars of positive peace are a well-functioning government, sound business environment, good relations with neighbours, free flow of information, high levels of human capital, acceptance of the rights of others, low corruption levels and equitable distribution of resources.

“You need to stimulate all eight pillars,” Killelea said. “It’s about building self-correcting systems. That’s how you get durable peace.”

For CEE, the GPI offers both a warning and a roadmap: militarisation alone cannot guarantee peace, and investment in cohesive institutions may prove the region’s most enduring defence.

Another striking GPI finding is the collapse in global peacebuilding. The share of military spending allocated to peacekeeping or post-conflict initiatives has fallen 35% in the past decade. The number of UN peacekeepers deployed globally has dropped 42%.

“It’s a false economy,” Killelea concludes. “If you don’t invest in peace, you won’t create peace.”