Exhibition director Tamas Revesz takes CET on a digital tour of World Press Photo 2021

Reading Time: 7 minutesTamas Revesz has organised the World Press Photo (WPP) exhibition in Hungary – the homeland of Robert Capa and Joseph Pulitzer – every year since the fall of communism. “It’s over 30 years – quite incredible,” the Hungarian photographer tells CET as he launches his 31st exhibition in Budapest. World Press Photo 2021 runs at the National Museum until October 31.

What makes a great World Press Photo?

When you are selecting from tens of thousands of images, how to choose is a delicate question. Categories help a little: we look at the importance of the events, the value and the quality of the images. A good, striking image catches your attention, moves you emotionally, has an excellent composition and – this is very important – doesn’t hurt the dignity of the person in the picture.

What do you think of this year’s exhibition? Is this a strong year?

When they nominate the picture of the year they showed six images and I was not sure that the “embracing image” would be the winner over, for example, the emancipation in front of the Lincoln Memorial, because of the very important Black Lives Matter story from the last year. Also another one of the Beirut explosion: that was perfectly done.

But at the same time, I understand that the COVID picture of the year tells so much. Really good news photography captures your attention in the very first moment, it tells only one thing, one very important thing, the Black Star agency founder Howard Chapnick once told me. When you look at this picture, it’s not that simple. You need to know what’s going on. You’ll need to read the caption. It has a double meaning, at least. I have some favourites this year, like the American gun collectors. There are more guns than people in the US and the pictures are really frightening and very strange.

For the really big museum posters, I used the sea lion swimming next to a face mask in Monterey. I love that it is at the same time the environment photo of the year but also COVID, so it includes everything to be picture of the year.

And there are so many complicated stories: the picture of the year, the Coronavirus story, is very nicely done and the website has a very good interview with the photographer. And one of the most complicated, Antonio Faccilongo, the Habibi (My Love) is a Palestinian story. A prisoner’s family are trying to keep alive the imprisoned family member and also, very strangely, they are smuggling out the semen of the prisoners to make babies.

There is another story which is from their long term story called Reborn. At first, you see very nice babies and then you realise that they are made of silicone. They are not really babies but a substitute for women who have had miscarriage or for men who want to have a baby playing – they are very distinct. I went to the museum today and I saw that people are really astonished, watching these stories. The exhibition is my baby, so I have to check it almost every day.

You are a long-standing WPP winner and organiser, but what did you learn about photography as a juror?

Being a jury member at the Word Press Photo was one of the biggest and most important schools for me in journalism – the debates and being together with legendary editor of Life and New York Times editor John G Morris, who published Robert Capa’s D-Day photographs in Life Magazine. Also Thomas Hoepker from Stern. We had long, long conversations.

Is Budapest a good venue for exhibitions?

This is the fourth year since I moved the exhibition from the Ethnographic Museum to Hungarian National Museum, because the other one was closed. This place is really beautiful: we have four huge rooms. The two years before COVID we had over 45,000 and then 50,000 visitors. It was the second most visited of the 120 locations worldwide per day, after Paris. Even during COVID last year, when there were limitations on numbers, we had over 20,000 visitors.

Were you the original organiser of the World Press Photo?

No, I’m the second. Eva Keleti brought the World Press Photo to Hungary. That was during the communist era so that was really a very tricky thing to do. She brought it for the first time to a so-called socialist country. I think it was in 1971 or 72, quite early.

How has the WPP changed in the last three decades?

Nowadays it is less bloody. It is more emotional. Visitors to the National Museum will see how strong the environment category is: for many many years it has been very strong. And even the hot news make you think about a question or the stories you see. Covid meant that it took the jury much longer – six weeks instead of two – even if so many new ways of communication work well. But the interesting thing about WPP is that it really helps you to understand the world and I think the success of these traveling exhibitions is that visitors can see authentic pictures on important matters. There are a lot of places where the freedom of press or views are not flowing so freely – in those places the WPP plays a more important role

Could we say there is a ‘Central European sensibility’ in photography?

I can’t tell you a really good answer, but it’s true that the visual sensitivity among Hungarian photographers is very high. If I look at my generation when we had really limited free expression until 89 – we had to read between the lines. Jozef Koudelka, a respected name in photography, was looking at my book on the Gypsies published in 1977 in Czechoslovakia and said “we couldn’t publish this here”. So freedom of visual expression was probably higher. They didn’t take it so seriously. Before my first important show in the Netherlands, on Gypsies, the Hungarian ambassador said “we cannot open this exhibition”. And of course we could, and there was not that much negative feedback. Rather, they were talking about how brave the Hungarian government was, to be facing these political and social questions.

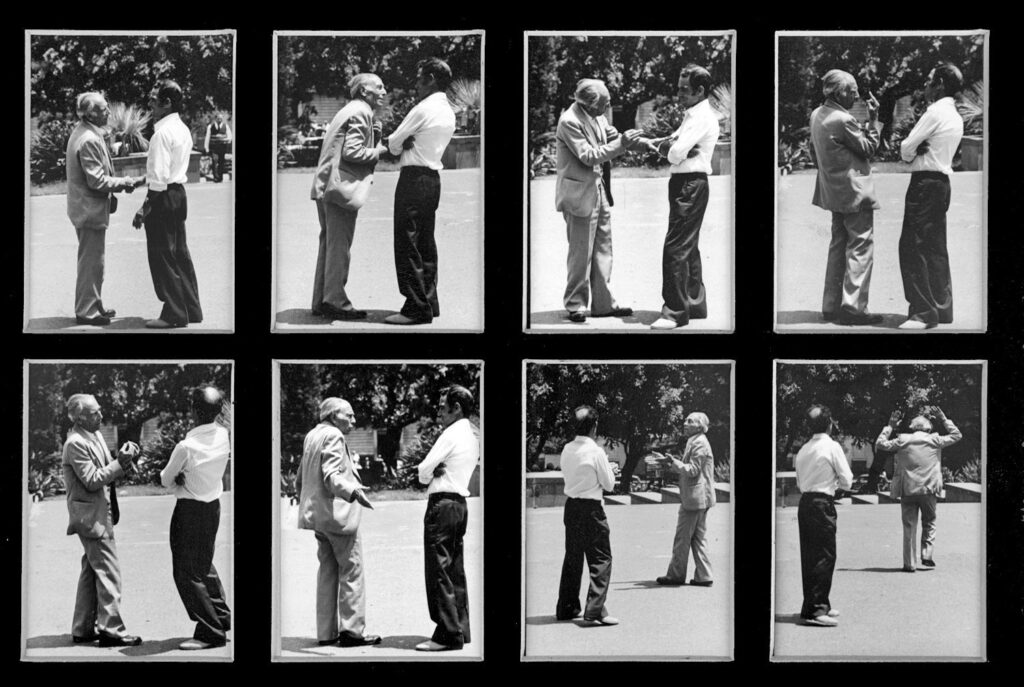

Italians © Tamas Revesz

Ginza, Tokyo © Tamas Revesz

NYC from New Jersey, Liberty Park (Cover of “New York”) © Tamas Revesz

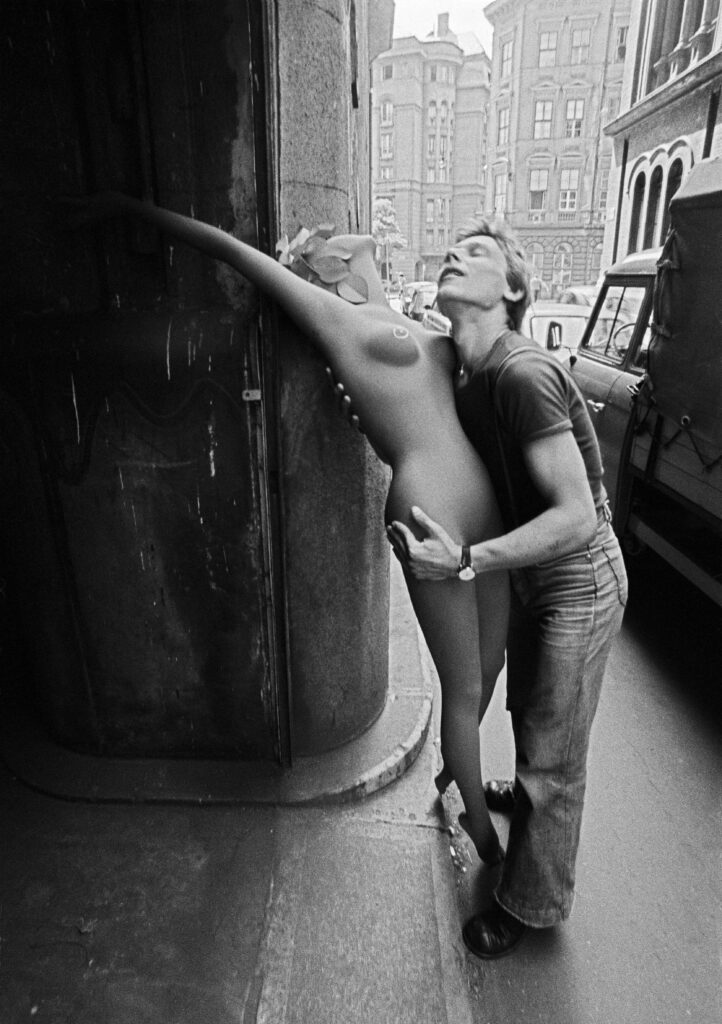

Love © Tamas Revesz

Leprosy on the Danube Delta, Romania 1991 © Tamas Revesz

Worship, Hungary 1978 © Tamas Revesz

Sleeping, Ecuador © Tamas Revesz

Gypsy Boy with Knife, Hungary © Tamas Revesz

Country, Hungary © Tamas Revesz

Palermo Paradise © Tamas Revesz

Dance © Tamas Revesz

Russians Leaving, Hungary © Tamas Revesz, World Press Prize winner 1991