Bulgaria at a Crossroads: Will it Leave Borissov Behind?

Reading Time: 4 minutesThe incumbent Bulgarian leader, Boyko Borissov, and his party, GERB, stumbled in the elections that took place on 4 April. For the prime minister, this meant losing his grip on the government after almost a decade of ruling the poorest EU member state. Three weeks after the inconclusive elections, the picture is still unclear: Will Borissov still have a say in the next government, or are early elections inevitable?

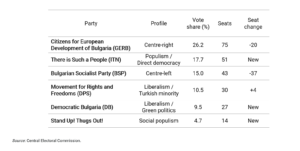

Having the most votes does not translate into election victory – this much is true for Boyko Borissov’s center-right GERB party, which won 265 of the votes; still, its share of the tally has fallen from one third to a quarter, the worst result in 10 years. GERB’s biggest competitor, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), lost even more supporters, in an election which has radically reshaped the Bulgarian political stage.

Bulgaria, an EU and NATO member country with a population of 7 million is carefully balancing its relations with both Russia and the West, and has a border with a regional military power, Turkey. As a member of NATO, Bulgaria is also responsible for NATO’s 354-km-long eastern border in relative proximity to Crimea. Its geographic position is one of the reasons while, despite multiple EU deadlines having passed and political promises made, Bulgaria is still waiting in the accession “waiting room” to be admitted into the Schengen area.

The country’s political stability has not been challenged in the last decade under Borissov’s rule, but the April election results may pose a serious challenge to forming a stable government. The real winner of the elections was a newcomer populist party, “There is Such a People” (ITN), coming in second with 17.7% of the vote. ITN, with its anti-establishment rhetoric, capitalized on diaspora voters and, in general, youth. The party is led by Slavi Trifonov, a well-known talk-show host and frontman of a famous pop music band. Lacking any political experience, Trifonov has refused to campaign or give interviews and is now coming to terms with the fact that his party has become the largest anti-Borissov political group.

The country’s political stability has not been challenged in the last decade under Borissov’s rule, but the April election results may pose a serious challenge to forming a stable government. The real winner of the elections was a newcomer populist party, “There is Such a People” (ITN), coming in second with 17.7% of the vote. ITN, with its anti-establishment rhetoric, capitalized on diaspora voters and, in general, youth. The party is led by Slavi Trifonov, a well-known talk-show host and frontman of a famous pop music band. Lacking any political experience, Trifonov has refused to campaign or give interviews and is now coming to terms with the fact that his party has become the largest anti-Borissov political group.

Democratic Bulgaria, also a newcomer green liberal party receiving almost 10% of the vote, successfully campaigned mostly in Bulgaria’s capital and actually beat GERB in Sofia. The third new, anti-Borissov party which made it into the parliament is “Stand Up! Thugs Up,” which gained 4.7% of the vote. The three newcomers and their strong anti-establishment line will make it difficult to form a stable government. Besides GERB and the socialists, the only party which remained in parliament is the Movement for Rights and Freedoms, a Turkish minority party, which has been a member of the Bulgarian parliament even since 1990, now gaining 10.5% of the vote.

What’s next then?

Concerning the possible outcomes of the government formation attempts, a local political expert speaking to the Central European Times sees three possible scenarios.

For the time being, Borissov has been trying to pull the strings in the background and attempting to form a “technocratic government.” On 14 April, former foreign minister Daniel Mitov was proposed as the country’s next prime minister. With this option, Borissov can buy time until another round of elections, which could be held in October 2021 along with Bulgaria’s presidential election.

If Borissov fails to convince any of the anti-establishment newcomer parties to form a coalition, another round of elections will be held in July. Experts find it highly unlikely that he will succeed: last year’s protests strengthened parties opposing GERB and their readiness for a compromise is low.

But one thing is clear: the new government will have to deal with burning budgetary issues. After delaying discussions with social stakeholders, the Borissov government hasn’t passed its recovery plan concerning the EUR 12.3 billion the country has been allocated from the European Recovery Fund. Furthermore, the country owes the EU a strategy on how it will spend the EUR 16.7 billion allocated from the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework. Given the current political deadlock, Borissov is using the recovery plan approval to pressure the opposition parties to accept his government’s version before the 30 April deadline given by the European Commission. The EC, however, has already signaled that any delay would not result in Bulgaria losing EUR 6 billion. Still, EU funds are seen by analysts as a strong incentive for the six parties to try to form a government in the shortest time possible.

How money is driving politics

As in most countries suffering the devastating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, Bulgaria is also in desperate need of generous public and EU funds to jumpstart the ailing economy. Bulgaria enjoyed a massive 6.4% yearly average GDP growth in the first decade of 2000. However, the 2009 global financial crisis hit the economy hard and resulted in a recession, followed by a whole decade of slow growth. Since 2010, under the reign of Boyko Borissov, the Bulgarian economy saw a 25% cent expansion.

But wealth is unevenly distributed. The financial and business life in the capital city of Sofia is dominated by a handful of ultrawealthy tycoons and oligarchs. European institutions often point out that a large number of public tenders, and projects financed from EU funds goes to the same business interests. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Index, Bulgaria ranks 69th. In 2020, social and economic disappointment led to large and long-lasting demonstrations in Sofia and across the globe among the Bulgarian diaspora, which resulted in a painful election loss for Borissov. Now the question is, who takes over?

Politicians – however challenging the current situation is – may rely on a positive and improving economic outlook for the Bulgarian economy. Fitch Ratings in mid-February revised the outlook on Bulgaria’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating (IDR) from stable to positive. That assessment reflects the dissipation of macroeconomic risks stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic, underpinned by a more resilient economy and a sound policy framework, as well as continued gradual progress towards euro adoption. According to their analysts, short-term downside risks related to the COVID-19 pandemic and an uncertain electoral outcome are largely offset by prospects of substantial funding for investment from the European Union and broad commitment to macro and fiscal stability.