Batteries are powering CEE’s e-mobility transition – CET analysis

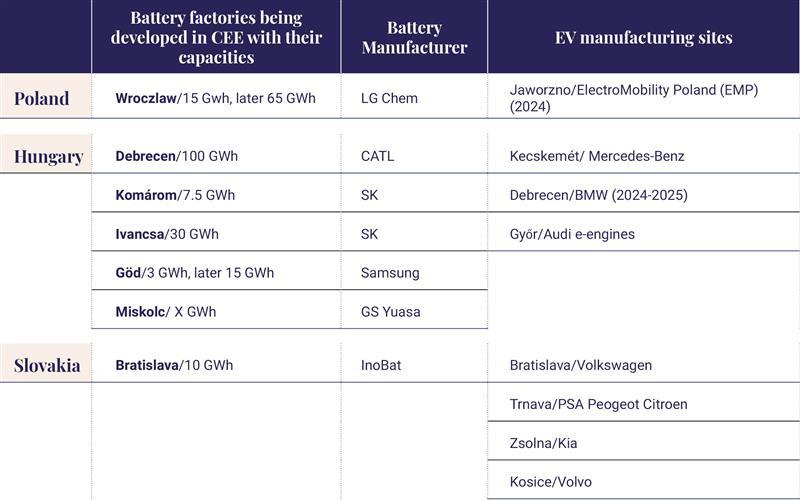

Reading Time: 7 minutesAs the EU accelerates its shift to electric vehicles by outlawing internal combustion engines by 2035, the auto industries in Central Europe are transiting to e-mobility. Battery plants can play a key role in the absorption of manpower as conventional car making is phased out, while pulling in new electronic vehicle (EV) projects. Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is well located to host ‘gigafactory’ projects of large battery producers and Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs). Hungary could be set to lead the way in battery manufacturing in CEE with an overall capacity of more than 152 GWh, which would place the country second only to Germany in Europe.

“Never let a good crisis go to waste” may be a well-worn phrase, but it is as pertinent as ever. In 2020, the COVID:19 pandemic exposed European OEMs’ vulnerability due to dependence on Asian suppliers and markets. This year, the war in Ukraine and resultant sanctions has reaffirmed that proximity to core markets, and political stability offer more than low costs.

Consequently, Europe’s auto industry has looked for suppliers closer to home, often finding them in CEE countries that still offer both relatively low wages for high-skilled workers, and government incentives.

Meanwhile, a major transition is underway in the automotive industry, as the EU plans to shift to electric vehicles by phasing out internal combustion engines by 2035.

This is not necessarily good news for countries that rely on the automotive industry, including Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary, as manufacturing EVs is less labour-intensive than making conventional cars. Meanwhile a new race is on for EV production projects.

Battery plants can make up for at least a part of the jobs lost and, even more importantly, are likely to attract new investments as carmakers want to avoid transporting batteries long distances.

Hungary massive deal with China’s CATL potential game-changer

The world’s largest battery producer CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co.) in mid-August signed a deal with the Hungarian government to build a EUR 7.4 billion electric car battery plant near Debrecen, east Hungary, with a capacity of not less than 100 GWh. The project would make the plant the largest of its kind in the EU and put Hungary’s overall capacity – over 152 GWh – second only to Germany in Europe as a whole.

The project will occupy 221 hectares and employ around 9,000 people. The investment will spur electric vehicle manufacturing in Hungary, Hungarian Foreign Ministry state secretary Levente Magyar said.

BMW is playing a key role in Hungary’s 21st Century auto sector, as its new factory now being built in Debrecen, near CATL’s planned giga-factory. Meanwhile Mercedes Hungary has decided to expand its operation significantly in Kecskemet, central Hungary, with a EUR 1bn investment, and wants 50% of its portfolio to be electrically powered by 2025.

Markus Schafer, technical director responsible for development and procurement at Mercedes-Benz Group AG, called the project a milestone in expanding electro-mobility in Europe. Besides Mercedes-Benz, CATL also plans to supply nearby BMW, Stellantis and Volkswagen with batteries.

Hungarian Sinologist Tamas Matura, who authored the recent “Chinese in Influence in Hungary” report at the Center for European Analysis (CEPA), however struck a cautious note on the CATL project when he spoke to the Central European Times. “There have been many grand announcements from the Hungarian government and China in the last decade, but in the event that this huge project gets done, it is indeed kind of a game changer,” Matura, who is an assistant professor at Budapest’s Corvinus University, told CET.

Noting that the project would double or even triple China’s current overall investment in Hungary, Matura highlighted three main obstacles for bringing the CATL investment to completion: energy, adequate labour force, and the environment.

The government has been talking about gigawatts of production capacities, they want to attract to Hungary, including the one near Debrecen. Citing energy experts, Matura said of all these factories were built “we would need another nuclear reactor with a 1GW capacity. So where would the electricity come from?” he said.

“I’m not sure that Russian energy supplies to Europe, will resume without any geopolitical consequences in the next five to ten years. So I think there are a lot of a lot of question marks about energy.”

Moreover, there have been issues regarding sourcing skilled workers in Hungary, Matura said, adding that “the plant would need thousands of people”.

Another question is over environmental protection issues, Matura said, “as the locals have already started to express their fears. We didn’t talk about this much in Hungary yet, but I think if the real construction starts or when installed, it will be a major question, especially to those living in the vicinity.”

CATL far from only Asian investor in Hungary

The second largest battery maker of the world, the Japanese GS Yuasa established a battery plant in Miskolc, east Hungary, in 2019 and the facility is now up and running.

South Korean battery manufacturer SK also intends to erect three factories in Hungary. A 7.5 GWh lithium-ion battery plant is already operating in Komarom, north Hungary, where another factory is about to be completed, with production set to start this year. SK has also announced a third plant in Hungary to provide nearby Daimler and Audi with batteries.

God hosts another Hungarian manufacturing site, where South Korea’s Samsung converted a television factory into a battery plant. Production is already underway, but the plant is expected to continue to expand capacity from 3GWh to 15 GWh.

According to Matura, “BMW has played a pivotal role in attracting these Chinese companies to Hungary, because Hungary is in the middle of the CEE automotive cluster, and many economists argue that the country is overly dependent on the automotive industry.

“The future of the automotive industry is more and more about electronics and software, and not hardware. While Hungarian higher education business doesn’t have the capacity to educate people who could work on the software side, it may lead to a situation where these investments, will technically increase the gross domestic product of the country, but not the gross national product,” Matura told CET.

Volvo invests to help Slovakia get ahead in EV production

Evidence of the above is provided by Volvo’s recent mega investment in Slovakia, where the company’s new facility is set to produce 250,000 EVs annually. Volvo has also lined up an adjacent site for future expansion where a battery factory could be erected.

Slovakia is currently leading the way in EV manufacturing with nine models in production or on the drawing board. Consequently, a battery factory of 10 GWh capacity is already planned in the Slovak capital of Bratislava, and set to begin production in 2024.

Slovakia-headquartered battery producer InoBat Auto and US EV specialist Ideanomics are expected to deliver up to 240,000 of batteries developed in a research centre in Voderay, west Slovakia. InoBat Auto is also planning a commercial-scale plant that will process scrap batteries to recover raw materials.

However, when the Hungarian government unveiled its deal with CATL last month, Slovak Finance Minister Igor Matovic compared Hungary favourably as opposed to his own country in a Facebook post.

Czechia – regional laggard, but with hidden potential

Czechia is currently lagging its regional peers in the ability to attract EV and battery projects, however, and the country’s carmakers complain that the Czech government has failed to prepare for the e-mobility transition.

While Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala called the EU’s Green Deal an “existential threat”, a spokesperson for the Czech Industry and Trade Ministry has commented that electric cars are not the only way to cut emissions, saying the country favours alternative fuels.

The Czech government is also reluctant to provide support to expanding EV-fleet and financial incentives for investments, unlike, for example, Slovakia, where one-fifth of the investment implemented by Volvo is covered by state support.

Now the Czech auto industry hopes that the government will step up efforts to secure a Volkswagen gigabattery project at a site near Pilsen, which would employ four thousand people. Volkswagen is now considering a location in Czechia and two elsewhere in Europe, possibly in Poland. While awaiting VW’s decision, Skoda recently started making battery systems for EVs at its plant in Mlada Boleslav, north Czechia.

South Korean firm, LG Chem, chose Wroclaw, west Poland, for its lithium-ion cells and battery plant, which currently has a capacity of 15 GWh, which is set to increase steadily over the coming years, to at least 65 GWh. LG’s batteries are installed in e-cars including Volkswagens, Renaults and Hyundais.

Lithium reserves could give Czechia, EU competitive edge

Czechia has a considerable advantage over other countries in the region: vast lithium reserves beneath the Ore Mountains: a raw material crucial to making batteries. However the Czech government has yet to decide on whether to proceed with the mining project next year.

Europe currently has only one lithium mine in Portugal, while most of its unrefined lithium need is currently imported from Australia, Chile, the US, and Russia.

To gain at least limited independence from external sources and reduce supply vulnerabilities, Europe must focus more on its own mining projects.

Portugal, Spain, Germany, Czechia, Finland and Austria could all offer viable lithium projects in the EU, but could meet with local resistance to mines.

Matura noted that although Czechia has enjoyed a “relatively good relationship with China in the past few years… the general rule has always been a quite tense relationship between Prague and Beijing. When it comes to Hungary, China has nurtured a relationship with the country, relative to its size.”