Poland tops employment rankings – OECD report

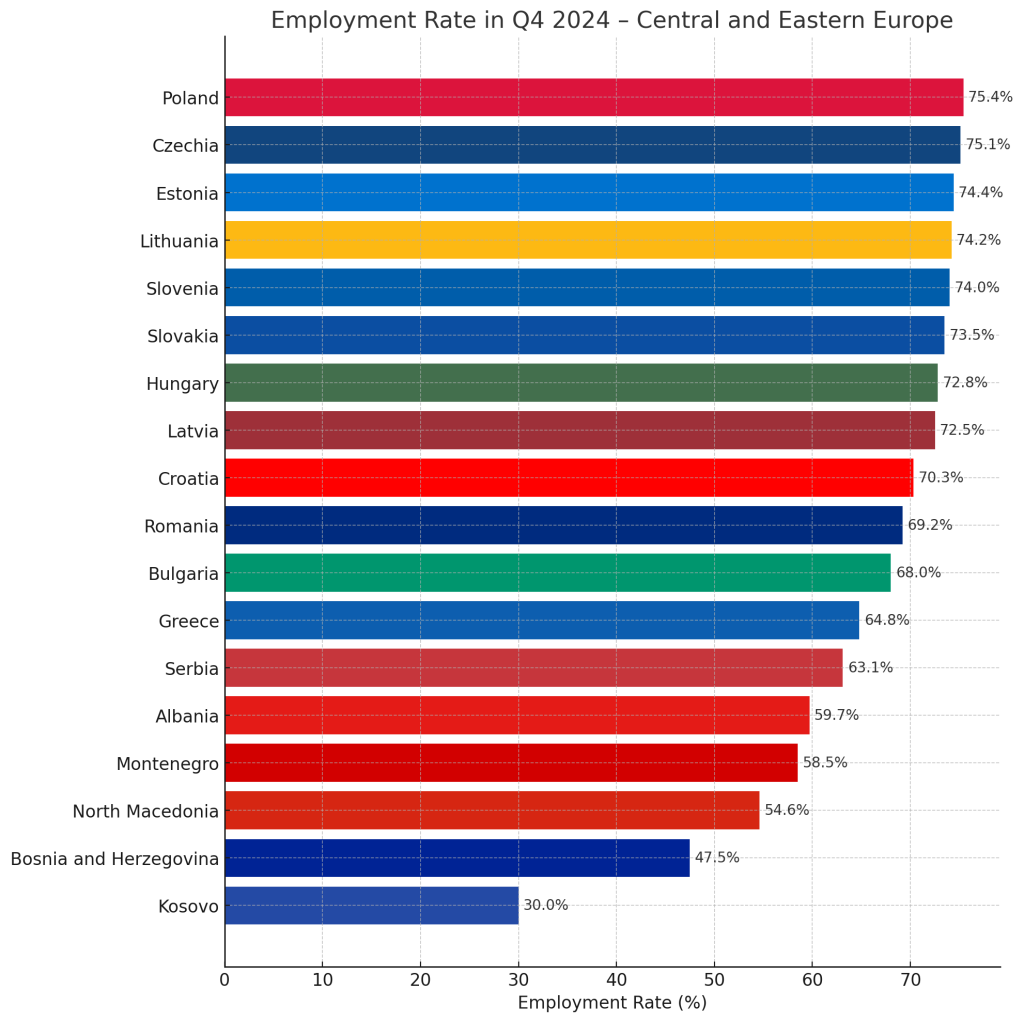

Reading Time: 3 minutesThe EU’s employment rate reached a record high of 70.9% in the fourth quarter of 2024, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). But while this marks a major milestone for the bloc, the picture in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is more complex, as it features record highs alongside persistent structural risks.

Czechia, Poland, Slovakia among top performers

Founded in 1961, the OECD aims to stimulate economic progress and world trade for 38 member countries that are committed to democracy and the market economy.

The OECD’s April labour market release noted that 27 out of the 38 members posted higher employment rates, with CEE economies such as Czechia, Poland and Slovakia among the top performers. Surging demand for industrial labour, a rise in female participation, and migrant workforce integration have helped drive rates to new post-2005 highs, the OECD wrote.

In Poland unemployment fell to 2.6% in February 2025, the lowest figure in the EU, although labour shortages increasingly constrain output. “It’s not just a matter of finding workers, it’s about retaining them amid rising wage competition,” one Warsaw-based HR director in the manufacturing sector said.

Czechia also reported robust growth, with employment now well above pre-pandemic levels, although companies face pressure to digitise faster as wage growth tightens margins. “The pool of available workers is drying up,” a Brno-based SME employer told Euronews. “We’re losing people to Germany and Austria, and local youth aren’t stepping into trades.”

Slovakia followed a similar trajectory, with rising participation driven by investment in automotive and electronics. However, gaps between urban and rural regions remain wide. In eastern districts, unemployment remains double the national average, according to the latest labour ministry figures.

Elsewhere in the region, Romania and Bulgaria saw smaller improvements. Both continue to grapple with large-scale emigration, particularly of skilled workers. From 2015-23, Romania lost over 1.8mn working-age citizens to net emigration, Eurostat data shows. The resulting labour shortages have hobbled domestic capacity in logistics, agriculture, and public services.

Youth employment up, but demographic issues loom

Across the wider EU, the unemployment rate fell to 5.7% in February 2025, the lowest since January 2000. Belgium and the Netherlands posted the highest job vacancy rates at 4.1%, driven by demand in construction, professional services and ICT. In CEE, vacancy rates remain elevated, with Slovakia, Czechia and Hungary all reporting difficulties in filling mid-skill technical roles, even as wage offers increase.

Despite the headline success, the OECD warns that Europe’s ageing population may curtail further employment gains. “The long-term viability of labour market growth depends on boosting productivity and participation among underrepresented groups,” the report said. Without reform, declining birth rates and rising dependency ratios could weigh heavily, particularly in CEE, where demographic decline is most acute.

A recent study by Eurofound highlighted gaps in youth employment, noting that while overall EU employment is up, younger cohorts still face barriers to stable work in many CEE countries. Meanwhile, women and older workers remain underrepresented in several local labour markets, suggesting untapped potential.

Governments across the region are under pressure to respond. In Hungary, the government has doubled down on pro-natalist family policies, but with limited short-term labour impact. Slovakia has announced new tax incentives for companies investing in worker training and automation. Poland is expanding residency pathways for Ukrainian refugees and other foreign workers to bolster supply.

However, analysts caution that these measures may not be sufficient. “The region needs a coherent strategy for the next decade,” one Prague-based labour economist said. “Without structural reform, current gains may prove fleeting.”