Large, integrated ICT boosts economies – CET analysis

Reading Time: 5 minutesEstonia has become the digital model for Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) due to a digitalisation policy that has seen it close in on the wealth and GDP of EU countries further west. The keystones of Estonia’s ‘CEE dream’ are increasingly recognised as public service digitalization and digital integration.

Estonia caught up with EU living standards 250% faster than Hungary from 2009-20, the latter country’s Central Bank Governor Gyorgy Matolcsy noted last year. The country so synonymous with digital culture that it also goes by the name of “e-Estonia” grew economically by over 40% in a decade, more than every other EU-27 country except Ireland and Malta.

Estonia makes startling progress on relative living standards

Meanwhile Estonia’s living standards climbed from 64.6% to 84% of the EU average. According to Matolcsy, the central bank governor known for espousing “unorthodox” economic policies, Estonia’s success has been built on a “service-based re-industrialisation supported by ICT and a full-scale digital transformation across all of the economy, and especially the governmental sector”.

Around two-thirds of this growth came from services, mostly ICT, Matolcsy claimed in an article last year. While the ICT sector is 8% in Estonia, it represents only 4-6% in the economies of the Visegrad Four countries (Poland, Hungary, Czechia and Slovakia). This was key in Estonia attracting the most tech investment in CEE and becoming its innovation leader, Matolcsy said. The Estonian strategy was to focus on digital transformation of public institutions and especially the government, as well as households, public administration and educational institutions.

Digital economy: a chance for emerging economies to catch up

Depending on definition, estimates of the planet’s digital economy range from 4.5-15.5% of global GDP, and the sector has grown 250% faster than global GDP over the last 15 years, according to the World Bank. As the digital economy is not resource-intensive, modern technologies have become relatively cheap and accessible to start-ups and multinational alike. Therefore, it serves as a playground in which emerging economies can successfully compete with developed ones, as long as the apposite policies are applied – and investments secured.

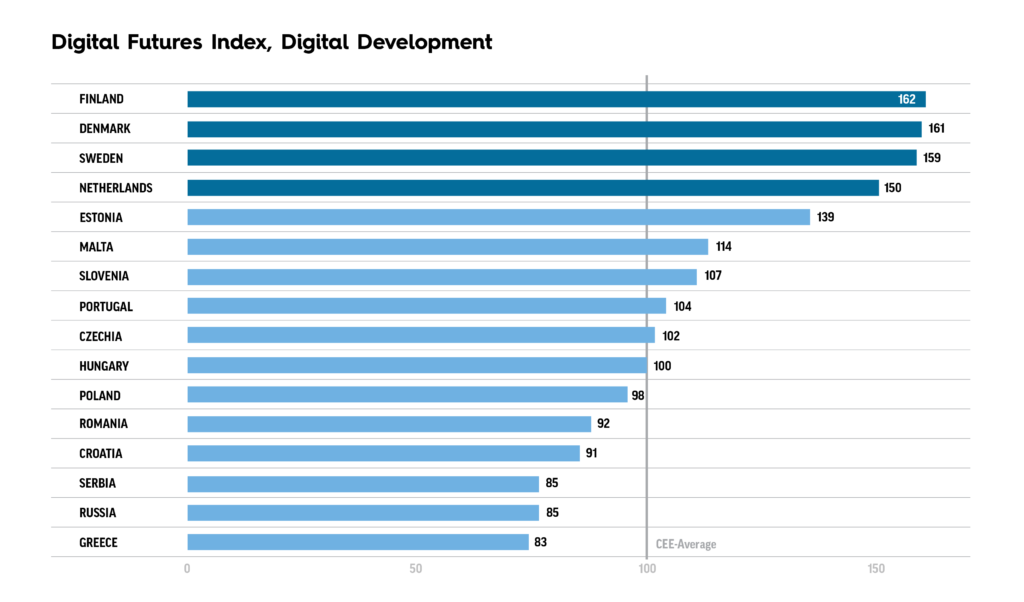

The Digital Futures Index (DFI) ranks countries of the region in terms of digital development and draws a direct connection between this and their wealth and competitiveness. It shows, CEE as a whole still lags Europe’s digital frontrunners like Denmark, Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands, but Estonia is rapidly catching up. Detached from its regional peers, Estonia has 132 index points on digital development, while Hungary scores the 100 average and Serbia, Russia and Greece bring up the rear with 83-85 index points.

Digitalisation of public services has discernible trickle down effect for ICT

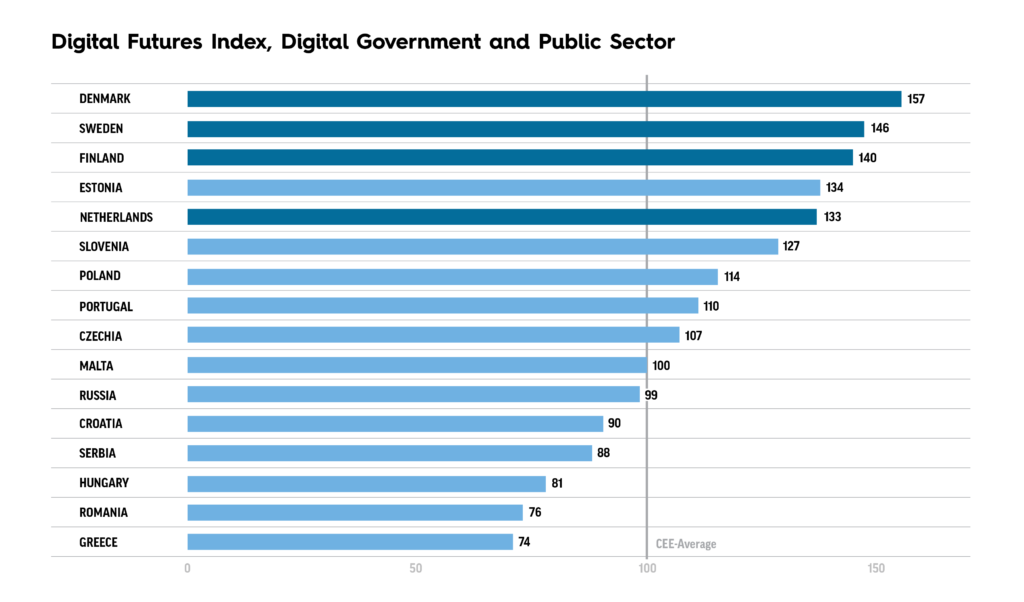

CEE economists like Matolcsy understandably want to know the key factors that play a decisive role in a country’s digital performance. According to the DFI, there is a clear correlation between digitalisation of public services and ICT development as a whole. Despite scoring highly on indices such as infrastructure, Hungary’s ranking was heavily impacted by its comparatively poor digitalisation of public services, demonstrating the importance of this attribute.

On the other hand, Estonia even outperforms the Netherlands, validating its strategy. “We have been keen to innovate and find the best solutions available globally to make them work in our digital government set-up and ecosystem,” Estonia’s Chief Information Officer Siim Sikkut told iTNews Asia. “We found it crucial to have a number of concrete building blocks as a foundation for the digital government,” he said, recalling the early 2000s.

DFI data demonstrates that governments can catalyse greater digital proficiency through digitising public services. This can encourage citizens to naturally grow competencies and become adept digital users. The more digitally proficient and engaged people are, the more they benefit from the digital economy. This in turn creates demand for more digital services, which enables people to do more, ad continuum. Estonia plans to further digitalise its public services and keep moving them to the cloud from a budget of EUR 97.43 million. A virtual assistant and platform named “Burokratt” is currently being developed to further ease Estonian businesses’ administrative burdens.

Technological integration has made Estonians digitally literate

But Estonia did more, by investing in e-commerce training for new entrepreneurs and active businesses via the County Development Centres network. The Estonian government also adopted an Artificial Intelligence Strategy for 2019-21, encouraging AI uptake by the private sector, enhancing business digitisation in Estonia.

According to the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), 48% of Estonian companies were using cloud services in 2021, almost double the EU average of 26%. In Estonia, 15% of firms use AI, as against the EU average of 25%. Estonia is 9th in the EU-27 regarding digital integration in business activities – to Hungary’s 26th – and boasts Europe’s highest number of unicorns per capita and a highly digitally literate population.

Digital can deliver significant GDP gains, overtake more traditional sectors

According to the latest DESI data – and somewhat contrary to Matolcsy’s argument – Hungary has a significant ICT sector in terms of its percentage of GDP: above 5%, and only just behind Estonia with its 5.6%. This is larger than Hungary’s automotive industry, which has a share of around 4% of GDP. Therefore, a sizable ICT sector would offer GDP and convergence gains comparable to that of Estonia, if more businesses in Hungary invested in new technology and integrated it into their business activities.

McKinsey estimates the value digital economy can add to Hungary’s GDP by 2025 at EUR 9 billion. This would represent a rise to 11% of GDP. However, the consulting firm projected a much bigger digital economy growth of EUR 26 billion, 16% of GDP for Czechia by 2025. ICT as percentage of Czech GDP is comparable or larger than the Hungarian one, but more importantly, it ranks 15th on the integration of digital technology, according to the DESI. In short, Czech businesses make better use of technology: 60% of the Czech SMEs have at least a basic level of digital intensity, to Hungary’s 49%, and score higher in digital public services.

Czechia shows great ICT promise

With a score of 107 for digital development, Slovenia outscores Hungary by 7 points, predominantly on digital public services and ICT skills. This means R&D investment from private companies in Slovenia is ranked at 142 index points, above Europe’s digital frontrunners. Slovenians are more digitally competent – including a highly skilled tech talent-base – and have greater gender diversity in the ICT sector. According to McKinsey, Slovenia, which has a smaller economy and even a proportionately less significant ICT sector (around 3.5% of GDP), a focus on further digitisation could generate an additional EUR 2.1 billion by 2025.

Czechia’s population is around the same as Hungary’s but as the country has a larger economy and more integrated ICT, there is a huge difference in McKinsey’s projection of 9 against 26. This disparity is even larger than the size of the two economies would suggest, as is the 11% vs. 16% projected GDP share.

In conclusion, countries with a sizeable ICT sector can boost their economies only when businesses increase digital intensity. Governments can likewise stimulate integration of digital technologies by digitalising public services and supporting training and STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education, in tandem with private companies and academic institutions.