Global minimum tax plan makes progress

Reading Time: 2 minutesThe Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Biden administration have brokered a compromise on the plan to introduce a global corporate tax regime with the three low-corporate tax states that had been holding out on the agreement. With Ireland, Estonia and Hungary now onboard, the ambitious measure to deter multinationals from accounting through low-profit jurisdictions looks increasingly viable.

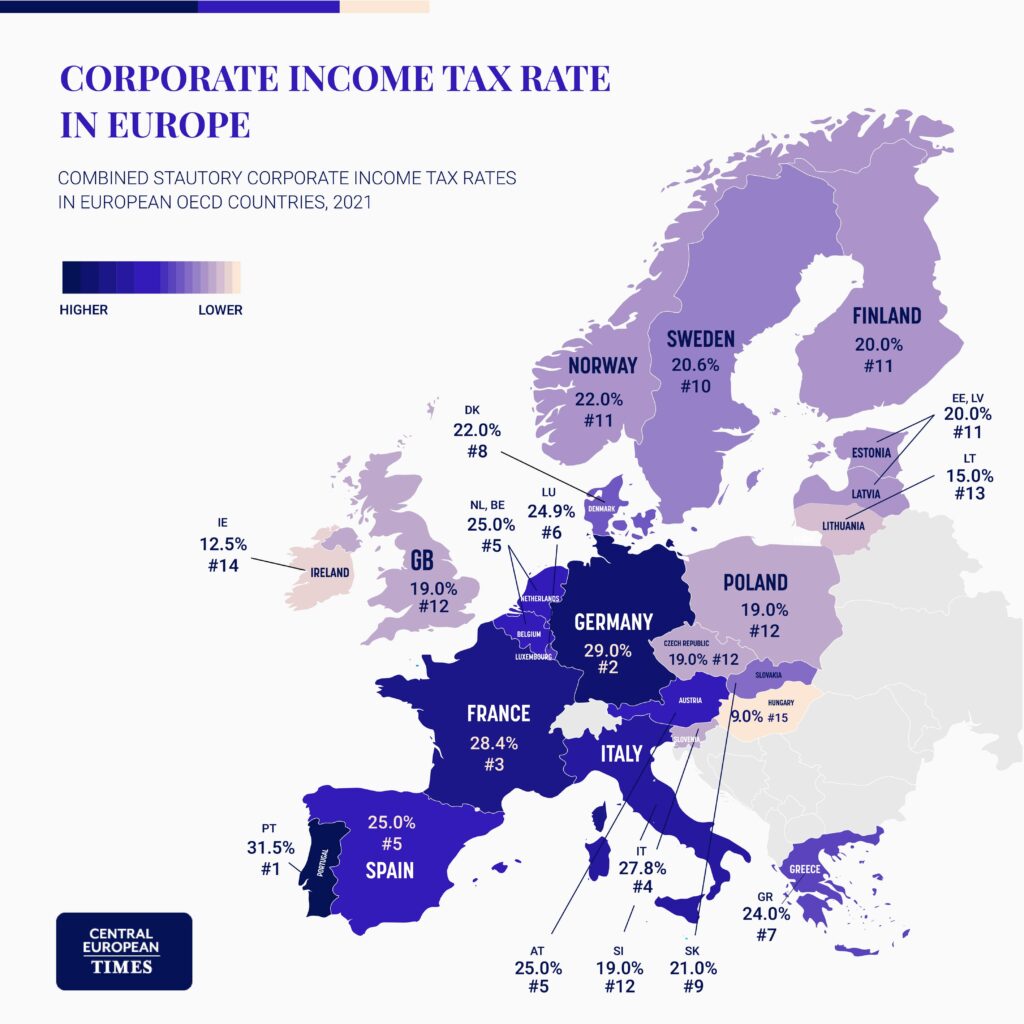

The three hold-out countries all leveraged concessions into the agreement. Hungary’s finance minister Mihaly Varga said Hungary’s corporate tax rate – at 9%, the lowest in the EU – will remain, while a “targeted solution” will collect the 6% disparity with the new global minimum rate of 15%. Ireland and Estonia have also been granted grace periods and other concessions, diluting the planned tax regime to an extent that is not yet clear.

Hungary has been granted a ten-year transitional period in which companies will be allowed to pay less tax, Hungarian Finance Minister Mihaly Varga announced. Writing on Facebook, he said over 100 amendments had been made to the original proposal for a global tax regime and as a result, Hungarian corporations will still pay 9%. Only actual business activity will be levied, while tax post-corporate assets and wages will be deducted from corporate tax with a “special calculation”. Varga also mentioned a “targeted solution”, the details of which have yet to be announced.

Ireland signed up after the minimum 15% requirement was dropped from the text. Moreover, the European Commission has assured Irish government that it can maintain its 12.5% rate for firms with an annual turnover of below EUR 750 million and also keep tax incentives for research and development. Irish Finance and Public Expenditure Minister Paschal Donohoe said “as a country matures, other factors such as the flexibility of our workforce and membership of the EU tend to become very important as well,” underlining that low corporate tax is not the sole benefit Ireland can offer foreign investors.

Estonia’s government highlighted that the OECD reform would only affect large global corporations and leave the Estonian tax system intact. The Baltic country also negotiated a four-year transitional period to allow local subsidiaries of multinational companies to adjust their operations and cash flows to the new regulatory environment.

Terminology such as the “targeted solutions” mentioned by Varga make a complete assessment of the plan difficult at present. However, the amendments suggest that loopholes in the global tax proposal have been accepted, allowing the three reluctant countries to integrate the global plan into their own taxation systems. It is also hard to predict the reaction of the corporate sector and to what extent amended global tax regulation will impact on the effective tax payable by companies, which could differ significantly from statutory rates.

Small and highly open economies have naturally been unenthusiastic regarding a minimum corporate tax higher than their own. On the other hand, well-established, large economies with low exposure to foreign markets have sought to moderate global competition for foreign direct investment, eliminate tax loopholes exploited by large – often tech – companies and secure resources for state-run economic projects. However, countries holding out from joining the agreement took different approaches, dependent on their level of economic development and benefits to foreign investors. While Ireland can offer economic fundamentals such as a skilled workforce, and robust legal and economic institutions, Hungary has had to counterbalance its extremely low corporate tax rates with high taxes on wages in a less stable environment, partly due to its frequent conflicts with EU institutions.