Russia-CEE Relations in 2021: Vaccine Diplomacy and Selective Engagement

Reading Time: 5 minutesDespite its historical dominance in Eastern Europe and geopolitical proximity to the EU, Russia remains a low-key trading partner for Europe, except when it comes to energy. Relations between Moscow and most EU member countries are best characterized as pragmatic, with both sides looking for mutual benefits and avoiding major confrontations.

But Russia, unable to compete with the EU either as a trading partner or an investor in the last three decades, has not given up on Central & Eastern Europe (CEE). Moscow is using every opportunity to boost its influence in the region, either as a key energy supplier, or, currently, through vaccine diplomacy, offering Russian-developed Covid-19 jabs to speed up inoculation campaigns and to show the EU’s weakness in coordinating efforts to contain the pandemic. Some CEE countries – like Hungary or Serbia – are more friendly towards Russian politics, while others – Poland or Romania – show less sympathy.

Russia’s selective involvement in the region is helped by the European Union’s apparent lack of a clear strategy vis a vis Russia. Not much is expected to change on that front in 2021, either. Even the latest EU sanctions agreed by the foreign ministers at the end of February in connection to the imprisonment of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny most probably will turn out not to pay much more than lip service to the issue. Political relations also recently hit an all-time low when EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell visited Moscow in early February and stood by speechless as Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov called the EU an unreliable partner.

But political turmoil has little impact on economic relations. Russia’s largest trading partner is the European Union: around half of all its exports are directed to Europe. On the flip side, Moscow is the 5th-largest partner for the EU, accounting for 4% of overall EU exports and 7 % of EU imports. In 2019, imports to the EU from Russia reached EUR 144 billion and EU exports to Russia totaled EUR 88 billion – though since then, trade has significantly fallen. The latest trends show a further drop in the EU27-Russia trade balance, EUR 4.519 billion less in January 2021 than a year earlier, and a significant decrease of EUR 2.349 billion from December 2020.

But political turmoil has little impact on economic relations. Russia’s largest trading partner is the European Union: around half of all its exports are directed to Europe. On the flip side, Moscow is the 5th-largest partner for the EU, accounting for 4% of overall EU exports and 7 % of EU imports. In 2019, imports to the EU from Russia reached EUR 144 billion and EU exports to Russia totaled EUR 88 billion – though since then, trade has significantly fallen. The latest trends show a further drop in the EU27-Russia trade balance, EUR 4.519 billion less in January 2021 than a year earlier, and a significant decrease of EUR 2.349 billion from December 2020.

With an overall trade volume of EUR 54.5 billion, Russia’s main EU partner is Germany: in 2019, imports comprised EUR 27.8 billion and exports EUR 26.6 billion. However, Russia’s contribution in trade relations with Germany is relatively low: 6.8% in its all extra EU imports and 4.2 percent in its extra EU exports.

In the CEE region – and despite political hostilities between the two – Poland is Russia’s biggest trading partner, importing EUR 14 billion (which makes up 17% of Poland’s extra EU imports) and exporting EUR 7 billion (12% of the country’s Extra-EU exports). Countries with the greatest dependence on Russia among their imports are: Finland (43% of its Extra-EU imports), and the three Baltic States: Lithuania: 43%, Estonia: 35%, Lithuania: 27%. On the export side, Latvia and Lithuania still export over a third of their Extra-EU goods to Russia. Among the Visegrad 4 countries, apart from Poland, Hungary and Slovakia are the most trade-dependent on Russia, especially on the import side, with 15% and 19.6% of all Extra-EU imports coming from Russia), while Czechia’s figure in this respect is only 7%.

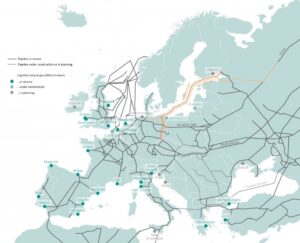

The relatively high import ratios are due to the region’s dependency on raw materials from Russia, especially gas and oil. Despite efforts to diversify Central Europe’s energy supplies, Russia is still a pivotal player in the region.

In early January it was a year since gas from Russia began to flow through the TurkStream offshore gas pipeline to Europe. Since the inauguration of TurkStream, two additional sections of the pipeline in Bulgaria and Serbia have been realized, though the latter has suffered a few months’ delay before the start of Gazprom’s gas transfer to the western Balkans and Central & Eastern Europe. In the meantime, in the north of Europe the readiness of Nord Stream II, another gas pipeline built to transport Russian hydrocarbons to the EU, stands at 95%. Pipe-lay is now underway in Danish territorial waters and will soon reach German waters, although German authorities are now investigating environmental organizations’ complaints, upholding a suspension of prior pipe-lay authorization for the project.

Besides energy politics, the EU is likewise consistent in supporting Russian environmental protection initiatives, cooperating, for example, in the Baltic Sea region. The EU is keen on and seeks opportunities for collaboration given that the ecological and climate effects of industry know no borders. Such cooperation entails numerous opportunities for European and Russian businesses.

Vaccine Diplomacy

Similar to its energy policy, in recent months Moscow has courted the goodwill of EU governments with its Covid-19 vaccine, Sputnik V. Following the delays seen in the EU’s joint vaccine acquisition strategy, Hungary (within the EU) and Serbia were the first in the region to purchase and administer Sputnik V; in Slovakia, prime minister Igor Matovic had to resign for pushing strongly for the Russian vaccine, but German state Bavaria and Austria are both contemplating placing orders for Sputnik. Moscow’s “vaccine diplomacy” approach has thus shown only mixed results so far.

“For political reasons, Poland, Ukraine, or the Baltic states will not get the vaccine from Russia. Knowing the conditionality of such aid – the side effects may be worse than the drug itself,” explained foreign policy expert on Russia, Agnieszka Legucka to Euractiv.

Economic relations: “Game of games” with remaining neighboring countries

Given the status of relations with the three Baltic states and Poland, Moscow has stood firm in developing relations with other countries in the Eastern Bloc, inside and outside the EU. Regarding Ukraine, the Russian government has worked to build on regional divisions following local elections in 2020 – effectively resulting in a strengthening of pro-Russia attitudes and businesses in the country. Russia has to compensate for losing ground in Belarus and in Moldova, too – given the political instability of the former and the election win of the pro-EU president, Maia Sandu, in the latter. The Moldova issue is likely to sour further traditionally difficult relations between Russian and Romania, a country on the edge of the Russian sphere of interest, but one which is much less dependent on its gas and oil than its surrounding neighbors.

On the flip side, Serbia, in particular, whose economy was least hit by the Coronavirus in the western Balkans given its limited exposure to international tourism, might be open to Russian investment. Besides the aforementioned TurkStream terminal in Serbia, Belgrade plans on privatizing 21 state-owned companies this year.